Cities

“I made house calls in East Baltimore as a practicing physician from 1984 to 2002. The problems I saw in patients’ homes are the same ones you would see among impoverished urban populations across the U.S.: hypertension, diabetes, asthma, cardiovascular disease, substance abuse. ”

Dean Emeritus Michael J. Klag, MD, MPH ’87

Since the establishment of the first cities more than 5,000 years ago, humanity has followed a steady arc of increasing urbanization. The clustering of populations spurred historic advances in education, government and scientific knowledge, but progress did not come without cost. As cities grew, inadequate sanitation and a poor understanding of disease allowed illnesses like measles, smallpox and cholera to thrive. In many modern cities, air pollution, gun violence and poverty contribute to health disparities.

Looking ahead, most urban growth will occur in Asia and Africa, creating more megacities of 10 million-plus. In developing countries, these outsized urban areas are often burdened with overwhelming public health, economic and infrastructure problems.

Cities’ continuing explosive growth presents immense challenges. The School’s urban-focused global research and action—in tobacco control, road traffic injuries, health care capacity and more—reflect a deep commitment to the development of healthy cities in the 21st century.

Timeline

1921

1921

At the newly established Peking Union Medical College, John Black Grant, DrPH ’21, sends public health students to do field training with police and health officers in the city’s health demonstration districts.

1937

1937

Abel Wolman, who co-developed a safe water-disinfection process using chlorine, is appointed chair of Sanitary Engineering at JHSPH. He designed Baltimore’s municipal water and sewer system and consulted on water projects worldwide.

1962

1962

The School appoints George W. Comstock, MD, DrPH ’56, director of the Training Center for Public Health Research in Hagerstown, Maryland, where he pioneers methods for community survey research and large cohort studies of chronic disease.

1968

1968

After riots engulf Baltimore following the assassination of civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., JHSPH students teach anti-violence courses at the Freedom School.

1970

1970

During a cholera epidemic in a refugee camp in Calcutta, India, JHSPH faculty administer oral rehydration therapy (ORT) to save thousands of patients who cannot be hospitalized. ORT ultimately prevents millions of deaths and becomes the standard pediatric treatment for cholera and other diarrheal illnesses.

1994

1994

With the cooperation of Baltimore Mayor Kurt Schmoke, JHSPH Epidemiology faculty apply their research on HIV transmission via intravenous drug use to establish what becomes the nation’s largest needle exchange program.

Then & Now

Then: Pioneering Urban Health

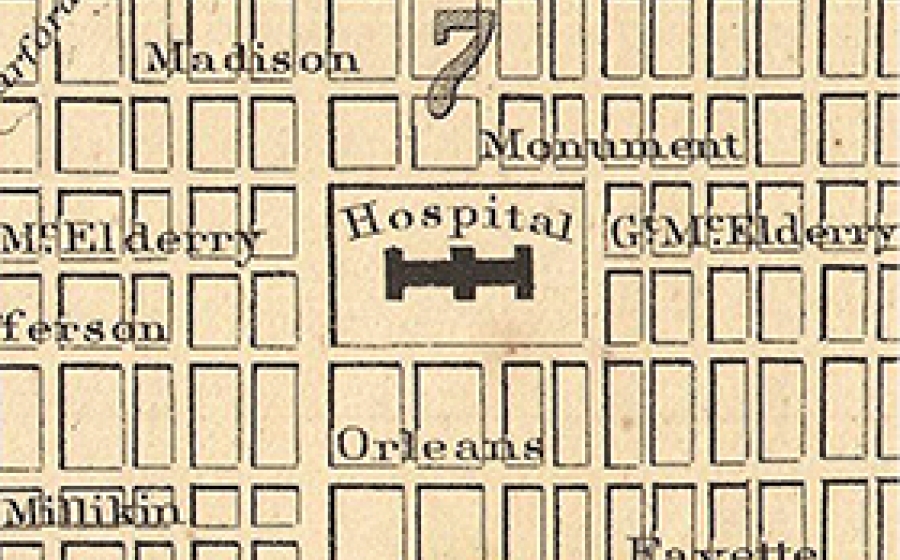

THE ONE-SQUARE-MILE EASTERN HEALTH DISTRICT (EHD) was established in 1932 by the School and the Baltimore City Health Department as a national model for public health research, training and administration. The School’s founding director William H. Welch envisioned this “population laboratory” of about 60,000 people “to be to public health training what the hospital was to medical training: the place where students could practice their professional activities under supervision, where scientific research could produce new knowledge, and where the population could also receive the best care and services available,” notes School historian Elizabeth Fee.

The EHD offered unprecedented opportunities for applied public health, with prenatal care, mental hygiene clinics and screenings for communicable diseases like syphilis and tuberculosis. Researchers studied infant nutrition, diphtheria inoculation and chronic diseases. Biostatisticians collected data on births and deaths and tracked morbidity, creating uniform medical records and coding for causes of death. Punchcard tabulating machines, then a new technology, advanced the budding field of biomedical computing.

The EHD created an unequaled population for study, providing practical field training for public health students, developing invaluable tools for subsequent epidemiological investigations and population research, and improving urban public health practices.

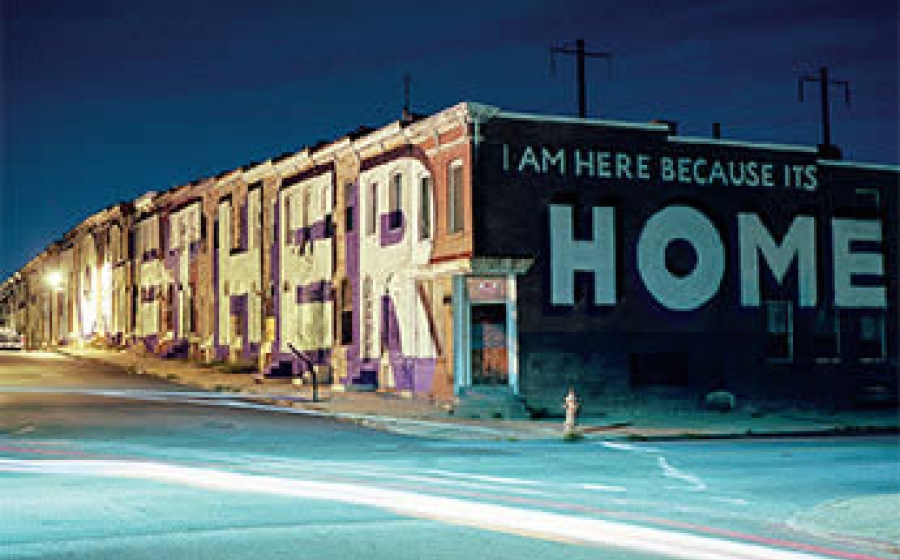

Now: Engaging Our City

BUILDING ON OUR LASTING COMMITMENT TO BALTIMORE, Bloomberg School faculty, students and staff continue to work daily to prevent teen pregnancy and infant mortality, stop gun violence, expand healthy food options and reduce injuries.

After the 2015 death of Freddie Gray sparked civil unrest and highlighted the city’s staggering inequalities, Dean Michael J. Klag, MD, MPH ’87, challenged the School to redouble its efforts. “Public health,” he declared, “has the tools and the focus to understand the source of inequity and discontent—including racism, economic disadvantage, social inequity and policing strategy—and to develop transformative solutions.”

With initiatives in departments and offices across the Bloomberg School, we recently launched Engaging Baltimore, an institution- wide effort to improve health and well-being in the city. Students for a Positive Academic Partnership (SPARC) works to improve health by addressing injustice. And the Student Outreach Resource Center (SOURCE) has matched thousands of volunteers with Baltimore community partners.

“Every part of the School is stepping up to strengthen its commitment to the city,” says associate dean Joshua M. Sharfstein. “There is a real sense of mission when it comes to Baltimore.”

A CLOSER LOOK

Teaming Against TB

In the ever-expanding shantytowns surrounding Lima, Peru, health care workers struggle with epidemics of tuberculosis and other diseases. International Health Professor Robert H. Gilman and his longtime colleagues at Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia were especially concerned about the 40 percent of HIV-positive patients who were co-infected with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. “Their mortality rate was 50 percent at two months,” Gilman recalls, “but it took four months to get test results that would tell us which drug therapy would work.”

They needed much faster diagnostics. When Peruvian microbiologist Luz Caviedes discovered that she could detect the morphology of multidrug-resistant TB by looking through a microscope, she and Gilman refined and validated the method, known as microscopic-observation drug-susceptibility (MODS). They published their findings in 2006, demonstrating that MODS is cheaper and more sensitive than other tests—with results in about a week.

Gilman has collaborated with researchers in Peru on studies addressing roadside pollution and asthma; infectious diseases related to climate factors; and water and sanitation projects, with a focus on Chagas disease, diarrhea and malaria. He is adamant that there is no substitute for being on the scene, where direct observation can inspire solutions. “The best way to understand the problem,” he says, “is to be surrounded by it.”

Display Credits

Main Illustration

- Dung Hoang

Other Content

- Longtime Connection (Phelan/Brailey) Duet Photo/Illustration: Chris Hartlove/Dung Hoang, Hopkins Bloomberg Public Health, Spring 2016

Then and Now

- Then: Eastern Health District Map: Mitchell’s New General Atlas, 1864 Edition

- Now: Engaging Our City: Patrick Joust

A Closer Look

- Robert Gilman: Larry Canner