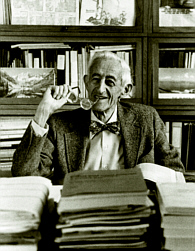

Abel Wolman

Kings, warriors, and artists may change the world, but Abel Wolman '13 changed water.

Before the Hopkins graduate and longtime professor developed a dependable water treatment method, a glass of water held not only the source of life but the risk of disease and death. In the early 1900s, waterborne diseases like typhoid fever and dysentery frequently sickened and killed people around the world. In the United States, one in 10 infants died in their first year of life, killed from typhoid or diarrheal disease. The cause: bad water. The solution, many scientists believed, was chlorine. But how much?

Enter Abel Wolman. After graduating with a BA from Hopkins in 1913, the 20-year-old East Baltimorean first began working with water by collecting samples of the Potomac River for the U.S. Public Health Service. After returning to Hopkins for a degree in 1915 from the new engineering school, he went to work for the Maryland State Department of Health. By that time, some cities in the U.S. and other countries had been trying to use chlorine to treat water. However, because water in different places had different levels of bacteria, technicians didn't know the appropriate amount of chlorine to use. A dose that might make one water source safe to drink could be too weak in another to fight off disease-causing microorganisms.

At the health department, Wolman and chemist Linn H. Enslow (a former classmate at Hopkins) developed a foolproof method of determining the appropriate dose of chlorine for any source of water. By taking into account the bacteria, acidity, and other factors (relating to taste and purity) of a specific water source, the pair could accurately set the chlorine dose needed to safely treat the water. The formula, still used today by water treatment plants around the world, ensures safe drinking water for millions of people. "Abel Wolman played a vitally important role in inaugurating the system that today provides Americans with some of the safest, cleanest drinking water available anywhere in the world," says Steve Gorden, president of the American Water Works Association.

The demise of typhoid fever alone in the U.S. reveals Wolman's impact: The number of typhoid cases per 100,000 people fell from 16.2 in 1913 to just 2.5 in 1936, according to AWWA statistics. A famous graph charts the decline of typhoid cases in the U.S. from 1900 to 1940 as water treatment expenditures increased. The "X" made by the decline in typhoid superimposed over the surge in water treatment plants inscribes the indelible mark Wolman made on human health.

But the energetic, 115-pound, 5-foot, 8-inch Wolman was hardly the type to coast. Instead, he spent the next seven decades immersed in work, first with the state and then the university, where he lectured and later served as chairman of the Department of Sanitary Engineering for 25 years. "He had an uncanny ability to help educate mayors, directors of public works, elected officials of [all] kinds wherever he worked," recalls M. Gordon "Reds" Wolman, Abel's son and a professor in the Department of Geography and Environmental Engineering.

While teaching new cadres of engineers and public health specialists, Abel Wolman also designed water systems in Baltimore, Detroit, Seattle, Portland, and other cities in the U.S. and advised the governments of Sri Lanka, Brazil, Israel, and more than 40 others.

A former president of the AWWA, committee member at the Atomic Energy Commission, and delegate of the World Health Organization, Wolman collected a slew of prizes, including the Lasker Award and the National Medal of Science. However, the awards and prestige were incidental for Wolman. "My obligation is to the common man," he told Hopkins Magazine in a 1982 interview. "My concern is the people."

Francis Montanari, an 82-year-old former colleague and friend, remembers Wolman as a gentleman and an intellectual who would show up in his later years to monthly luncheons with friends, always carrying an agenda of items to discuss. (Montanari also recalls Wolman's insistence on having hors d'oeuvres with a cocktail. "Now, those of us who remember, we call that 'wolmanizing,' he says.) Above all Montanari remembers his friend as a man who wanted to get things done. "He had little patience with people who didn't accomplish things," says Montanari, who began working with Wolman in the 1950s in Latin America. "He wanted action."

At Wolman's final international conference before his death in 1989, he spoke before more than a thousand sanitary and environmental engineers in Rio de Janeiro. As he walked to the podium, they gave him a standing ovation, Montanari remembers. And after Abel Wolman spoke, they rose to their feet again to applaud the 96-year-old marvel one last time.