What the Tuberculosis Outbreak in Kansas Means for Public Health

A TB outbreak in the U.S. often signals a need to strengthen the systems we rely on to keep case rates low.

The U.S. has one of the lowest tuberculosis incidence rates in the world. So when there are outbreaks of this bacterial infection, like the one reported last month in Kansas, they get our attention.

While the threat to the general public remains low in the U.S., TB outbreaks may reveal a deeper problem with public health infrastructure: Who is testing for TB? When a case is detected, who is collecting and sharing that information? Who is conducting contact tracing to identify asymptomatic cases and ensuring that infected people are being treated?

Globally, TB kills more people than any other infectious disease, largely because that public health infrastructure is lacking in some of the world’s most populous regions.

In this Q&A, David Dowdy, MD, PhD ’08, ScM ’02, professor in Epidemiology, provides an overview of tuberculosis, including how it spreads, who is most at risk, and what the Kansas outbreak suggests about the state of our public health infrastructure. This article draws from the February 4 episode of Public Health On Call and additional interviews with Dowdy.

What is tuberculosis (TB)?

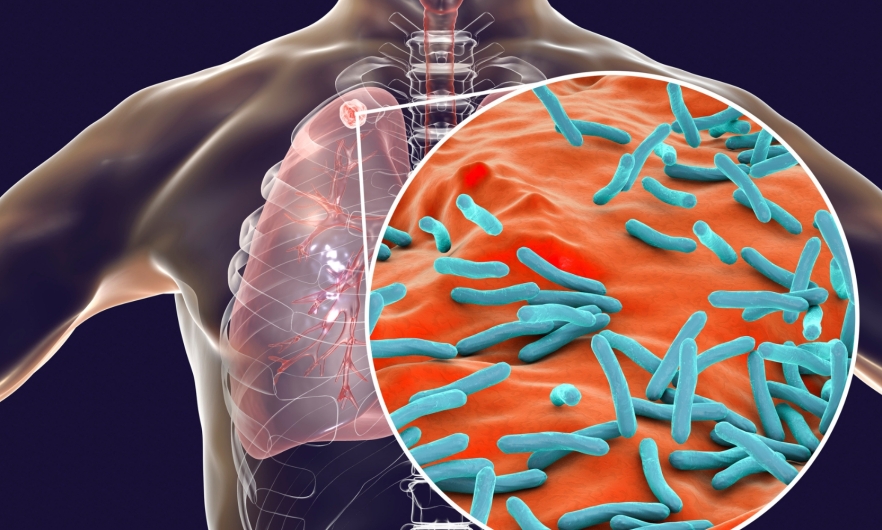

Tuberculosis is an infectious bacterial disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. TB has been around for centuries. Tuberculosis is the leading infectious cause of death worldwide.

How does tuberculosis spread?

Tuberculosis is spread through the air; it’s one of very few truly airborne diseases. As such, the TB bacteria can linger in the air for several hours and doesn’t require close contact to transmit.

That said, here in the U.S., the average person’s risk of becoming infected with TB in this way is quite low. That’s because in addition to historically low case rates, people in the U.S. tend to have better access to basic health needs like adequate nutrition.

Who is most at risk for tuberculosis?

People with compromised immune systems—whether due to another health condition, exposures like smoking and indoor air pollution, or inadequate nutrition—are at higher risk of becoming infected. Outbreaks of tuberculosis typically occur in tightly crowded settings like prisons and homeless shelters. Notably, these are also places where people often lack access to adequate health care and basic public health services.

We also see higher rates of tuberculosis among people who were born in or spent significant amounts of time in countries where rates of TB are higher.

What are the symptoms of tuberculosis?

Tuberculosis mainly affects the lungs, but infection can also spread to other organs. The first symptoms most people notice are fever, weight loss, night sweats, and cough.

Tuberculosis is distinct from infectious diseases that are more common in the U.S.—like COVID and the flu—in its time from infection to symptom presentation. For COVID or the flu, you often feel symptoms only a few days after being infected. With tuberculosis, the incubation period can be anywhere from a few months to many decades.

How do you test for TB?

When testing for TB disease—also called active TB—you generally need a sputum sample. People with TB disease generally have symptoms and are contagious, though it is possible to be contagious without having symptoms.

Latent TB means that TB germs are present in the body, but the immune system is keeping them in check and you don't have any symptoms. While people with latent TB aren't contagious, they are at risk of developing the disease later on—for example, when another illness or extreme stress puts additional burdens on the immune system.

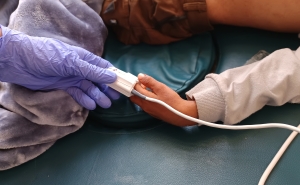

When we test for latent TB, we’re looking for the body's immune response to TB. This can be done using a skin test, where a small amount of tuberculin fluid is placed under a person’s skin using a needle. The firmness that results after two to three days is used to determine whether someone’s immune system recognizes TB. Latent TB can also be identified through a blood test.

Can an X-ray be used to check for TB?

X-rays are more of a screening tool for TB, or part of a larger diagnostic approach. An X-ray alone can’t confirm the presence of TB, but it can show abnormalities [in the lungs] that might warrant further testing. If a patient has a chest X-ray suggesting TB, they should then give a sputum specimen to test for TB disease.

Is there a vaccine for TB?

There is a vaccine for TB called BCG that is given to infants at birth in countries where TB is common. BCG is one of the most widely delivered vaccines in the world; it is generally not used in the U.S., where the risk of TB infection is low. However, while BCG is very effective against childhood forms of tuberculosis, it is not effective against the adult forms.

There are studies underway to evaluate whether revaccination with BCG can provide protection for adults who were vaccinated as infants. There are also studies in progress to evaluate potential adult and adolescent vaccines for TB. Those studies are showing some promise, but right now we don’t have a licensed vaccine that is known to provide protection to adults.

How is TB treated?

Active TB is treated using antibiotics—usually a regimen of four drugs taken for at least six months. Latent TB can be treated with a number of different regimens of preventative antibiotics: Taking two drugs daily for a month, two drugs weekly for three months, or one drug daily for four or six months.

What is the status of the outbreak happening in Kansas?

There is an ongoing outbreak of tuberculosis in two counties in Kansas. As of January 31, 67 cases of active TB and two deaths had been counted across these two counties, making it one of the largest outbreaks of tuberculosis in the United States in the past 30–40 years.

It’s important to note, however, that these cases did not all appear in January 2025. This outbreak has been going on for at least a year, possibly even longer. That’s partly because it often takes many months from the time of infection for a person to develop symptoms and TB disease. Then, there’s sometimes additional time between the appearance of symptoms and the actual diagnosis, and ultimately the recognition that there is an outbreak happening.

Does this outbreak signal something larger for U.S. public health?

Tuberculosis outbreaks are often indications of weakness in public health infrastructure. When public health services weaken, one of the first things you will see is outbreaks of TB. That’s because we've been successful in keeping TB levels in the U.S. so low. An outbreak of 60 TB cases is a real signal of deteriorating capacity, compared to an outbreak of 60 cases of a more prevalent infectious disease—such as gonorrhea or even HIV—which would never rise to the same level of attention.

We depend on our public health surveillance systems to identify TB outbreaks and respond quickly with contact tracing. From there, we need to be able to quickly test and treat anyone who has been in close contact with a person having TB; this includes people who test positive for latent TB so that we can prevent those people from developing TB in the coming years.

When we see larger outbreaks like the one in Kansas, it’s often the case that a small number of initial cases were identified and then more were discovered through contact investigations. That underlying public health system is essential to detecting and containing outbreaks at very early stages.

Should the general public be concerned about this outbreak?

In the U.S., the overall risk from tuberculosis is low. TB is a very serious and sometimes deadly disease, but it is not the most infectious of all diseases, and officials are doing everything possible to keep the current outbreak contained.

That said, this should be a reminder to all of us of how much our personal health and the health of our families and those around us depends on public health infrastructure. When public health capacity starts to weaken, we’re all at greater risk. While this one outbreak in Kansas is not an immediate threat to the rest of the country, it is an indication that our public health system is not as strong as it should be. Public health systems are the first line of defense against a number of diseases.

What does this outbreak represent in the current landscape of public health systems being under threat both nationally and internationally?

The U.S. is seen as a global leader in the fight against tuberculosis, leading the charge in research and development. Even among other Western countries, TB rates in the U.S. have historically been very low. Yet for two years in a row now, rates of tuberculosis in the U.S. have increased. That’s something we haven’t seen in decades.

This should be a wake-up call for us. With fewer public health officials and with aging technology and reporting systems, we will start to see more outbreaks like this. These sentinel events provide an indication that our public health system is being stretched thin.

Aliza Rosen is a digital content strategist in the Office of External Affairs at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Related:

- The Other Pandemic: Why TB Deserves Your Attention

- Overcoming Barriers to Tuberculosis Care in the DRC

- Tuberculosis in the U.S. (podcast)

More from the Bloomberg School

- See latest headlines

- Learn more about our departments: