The Science of Vaccine Safety in the U.S.

Clinical trials, government agencies, and data systems ensure vaccines meet high safety standards.

As with any drug or medical product, when we decide to take a vaccine, we want to feel confident that its benefits outweigh any possible risks.

Scientists and public health researchers take those questions and concerns seriously, especially in an age when mis- and disinformation about vaccines has caused people to question one of public health’s biggest achievements. In the U.S., vaccines are evaluated through multiple intertwining systems to ensure they are safe and effective.

As part of Public Health On Call’s Vaccines 101 series, Daniel Salmon, PhD ’03, MPH, a professor in International Health and director of the Institute for Vaccine Safety, spoke with Josh Sharfstein, MD, about the science behind vaccine safety. He explains the high standards for vaccine safety in the U.S., the ways government agencies and public health researchers study and monitor vaccine safety, and opportunities to further strengthen safety. This Q&A is adapted from their conversation.

When are vaccines evaluated for safety?

Vaccine safety is considered at every point in the process of vaccine development and use—from the time scientists even consider developing a candidate vaccine, to the testing that takes place in animals, laboratories, and clinical trials. Safety monitoring continues even after a vaccine is licensed and used in millions of people.

Compared to drug and medical device safety, how is vaccine safety unique?

The standards for vaccine safety are even higher than for drug safety, for a few reasons:

- What they’re used for: Vaccines are generally given for prevention, whereas drugs are given as treatment.

- The health of the recipients: The people receiving vaccines are generally healthy.

- Risk tolerance: Regulators’ tolerance for risk or adverse reactions is much lower for vaccines. Because vaccines are meant to be given to so many people, even a rare adverse reaction could impact a large number of people.

- Who they’re for: While a drug is designed to treat a specific condition, vaccines are intended for everyone, or at least everyone in a specific age group—all children, or all adults, for example.

The standards for vaccine safety are even higher than for drug safety.

The wide range of people a vaccine is intended for also makes safety assessment more complex. When a drug is developed, it is often intended for a defined population—people with a specific medical condition or people with specific comorbidities—so you know who you need to study it in to ensure its safety. With vaccines that are given universally, it may affect certain subgroups differently, and it can be harder to represent all of those variables in trials. That's why it’s important to monitor safety even after vaccines are approved.

How do you determine whether something a person experiences after receiving a vaccine is actually caused by the vaccine?

That’s one of the biggest challenges in vaccine safety science. Bad things happen to people every day, regardless of whether they receive a vaccine. If you vaccinate a large number of people, by chance alone, bad things will happen to some of them after getting the vaccine. In vaccine safety science, we aim to determine whether an event is causal—a result of receiving the vaccine—or coincidental.

When people get vaccinated and then experience a medical issue, it's tempting to blame the vaccination. But it’s important for us to determine whether that medical event was caused by the vaccine or coincidentally happened afterward with no connection to the vaccine.

Clinical trials play a big role in this. The large Phase 1, 2, and 3 clinical trials conducted before authorization or licensure are randomized and blinded, and randomization is very useful for causal inference. If you see a higher incidence of a medical issue in a randomized vaccine trial, you're much more able to say it was caused by the vaccine. That said, even with the tens of thousands of participants, vaccine clinical trials have limitations. If a reaction is rare, occurs in a specific subpopulation, or has a delayed onset, it’s not going to be identified during a clinical trial.

Once vaccines are licensed or authorized and used widely, we look at what happens in the real world, when millions of people are vaccinated.

The weight of evidence clearly does not show an association between vaccines and autism.

How is vaccine safety overseen in the U.S.?

Following development and testing of a vaccine, the FDA, with input from its Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee, decides whether to approve or authorize it.

Once a vaccine is authorized or approved, the responsibility for safety is shared between the CDC and the FDA. The two agencies manage a passive surveillance system called VAERS, the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System. Any person can report anything to VAERS, so with very rare exceptions,, you can’t tell if an adverse event reported through VAERS is truly causal or coincidental. But it can act as a warning system.

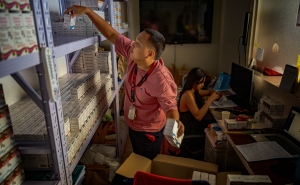

Other monitoring efforts include the FDA’s Biologics Effectiveness and Safety System, V-safe, a CDC tool that emerged through the COVID pandemic, and the CDC’s Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) project. The Johns Hopkins Institute for Vaccine Safety is one of several CISA project sites that work to understand the biological factors that increase the risk of adverse reactions in some populations.

There are also a number of systems that collect data that help researchers and public health professionals monitor vaccine safety, separate causal events from coincidental ones, and make informed decisions about vaccine recommendations and schedules. The Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD), a collaboration between the CDC and health care organizations, is the most widely used. The government also has several different systems that support vaccine safety monitoring, including the Indian Health Service, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the Department of Defense.

How do you approach the allegation that childhood vaccines cause autism?

There have been 16 well-conducted epidemiological studies—done by different investigators, in different countries, using different methods—and all 16 of them find no association between vaccines and autism. In science, it’s very hard to prove a negative, so you have to look at the weight of evidence, and the evidence is pretty compelling. And the weight of evidence clearly does not show an association between vaccines and autism.

How can the U.S. further strengthen its vaccine safety efforts?

Large health care databases offer a huge opportunity for safety studies.

The VSD provides great data on about 3% of the U.S. population—roughly 11 million people. However, when you analyze safety concerns, researchers often look at certain subpopulations. When you break those 11 million into subgroups based on age and gender, the data sets get progressively smaller.

With the growth of electronic health records and large databases both domestically and globally, we could be combining and analyzing a lot more data to make more precise estimates of the risks of potential adverse effects.

There’s also a huge opportunity to further strengthen our understanding of why vaccine adverse reactions happen and among whom. With uncommon adverse reactions like myocarditis following a COVID vaccine or Guillain-Barré syndrome after a flu vaccine, we have historically struggled to understand why they happened and among whom. For every million people who receive a flu shot, there are maybe one to three cases of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Figuring out how and why it occurs could potentially inform vaccine development or screening practices to identify individuals who should not receive the vaccine, thus preventing the reaction altogether.

If there are opportunities to improve vaccine safety, does that mean that vaccines are not safe?

No, it’s an approach of continuous quality improvement. We do our best work with the tools and resources we have, but we always want to make systems better. As we make improvements in big data, science, and genomics, we should take advantage of the opportunities they offer.

This Q&A was edited for length and clarity by Aliza Rosen.

Related:

More from the Bloomberg School

- See latest headlines

- Learn more about our departments: