Measles Outbreaks in the U.S. Highlight the Importance of Vaccination

Measles is one of the most contagious infectious diseases. It is also vaccine-preventable. Experts worry misinformation and falling vaccination rates could cause more outbreaks in the U.S.

Editor's note: This article was updated on March 25.

A measles outbreak in the southwestern United States continues to grow as public health officials work to contain the spread and boost vaccination rates. At a time of rampant mis- and disinformation about vaccines, public health experts worry outbreaks like this may only become more common.

The current outbreak began in late January, and as of March 25, Texas has confirmed 327 cases—the majority in Gaines County—and 43 cases are confirmed in neighboring New Mexico. A death reported on February 26 is the first death from measles in the U.S. since 2015.

“Most of the cases are occurring in a Mennonite community that largely homeschools, so there would not be school vaccine mandates,” explains Bill Moss, MD, MPH, a professor in Epidemiology and executive director of the International Vaccine Access Center.

In this Q&A, he explains the key facts about measles, how it spreads, and why high vaccination rates are so important to keeping outbreaks from occurring.

What is measles?

Measles is a highly contagious disease caused by measles virus. It typically causes a cough, red eyes, high fever, and rash, but it can lead to more severe health problems.

Is measles dangerous?

Yes. Here in the U.S., about 1 in 5 unvaccinated people will require hospitalization from measles. In 2024, that rate was even higher—about 40% of people with measles were hospitalized. Measles can also lead to more severe issues, including pneumonia, encephalitis, brain damage, and pregnancy complications. Complications of measles can occur in anyone, including in healthy children and adults.

Scientists have found that measles wipes out the body’s memory of bacteria and viruses. This weakens your immune system, making you more likely to get sick from other diseases. This effect can last for years.

Measles can also be deadly. In 2023 alone, an estimated 107,500 people globally died from measles—mostly unvaccinated or under-vaccinated children under 5.

How does measles spread?

Measles spreads through the air and via droplets. You can get measles by breathing air contaminated by an infected person or touching an infected surface. The measles virus can stay in the air for several hours after an infected person coughs or sneezes; it does not require close contact with an infected person to transmit.

Measles is one of the most contagious infectious diseases. In a completely susceptible population, one person with measles will infect an average of 12–18 other people.

Who is at the highest risk for contracting measles?

Anyone who has not had two doses of the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine, or has not previously contracted measles, is susceptible.

In the U.S., this includes most children under 12 months old, before they’ve received their first MMR vaccine dose. There are also people who cannot receive the MMR vaccine and thus are susceptible to measles. This includes people with certain medical conditions or severe allergies, people who are immunocompromised, and people who are pregnant or planning to become pregnant soon.

At what age should my child get the MMR vaccine?

In the U.S., the first dose of the MMR vaccine is recommended at 12–15 months of age. Between 93% and 95% of children will be protected by that dose. The second dose is recommended at 4–6 years old, generally right before children enter kindergarten, and about 97% of children will be fully protected following that second dose.

Can a child get the MMR vaccine earlier than 12 months old?

The MMR vaccine can be given to children as young as 6 months of age. The CDC recommends children 6–11 months receive the MMR vaccine before traveling internationally, but it does not provide clear guidance for outbreaks in the U.S. An MMR vaccine given at 6–11 months is given in addition to the two recommended doses, not as a replacement dose.

If you live in or will be traveling to an area in the U.S. where an outbreak is occurring, talk to your pediatrician about whether your young child should receive a dose of the MMR vaccine outside of the recommended schedule. This can also include children who have received their first recommended MMR dose but are not yet at the recommended age for their second dose. According to the CDC, it is possible to get a second dose earlier, as long as it is at least 28 days after the first dose. Your health care provider can help you weigh any factors that could increase your child’s risk of exposure to measles, including measles activity and vaccination levels in your local community.

If the measles shot is so effective, why do I keep hearing about people getting sick from measles?

The problem is that not everyone is vaccinated. Because measles is so contagious, it relies on at least 95% of a community to be vaccinated. In the U.S., about 91% of U.S. children ages 19–35 months have been vaccinated. However, coverage in some communities is much lower, putting them at greatest risk.

Why have U.S. measles vaccination rates dropped in recent years?

There are a number of compounding factors, one of which is actually how effectively we’ve vaccinated against measles in the past. Strong immunization programs undermine themselves: When vaccination rates are high, the disease goes away. As a result, people aren’t as concerned about it and don’t see the necessity to vaccinate.

Every parent wants to make the right decision for their child. Between the historically low rates of measles in the U.S. and the prevalence of mis- and disinformation about childhood vaccines, some parents underestimate the risk of measles and overestimate the risk of the vaccine.

Is the measles vaccine dangerous for my kids or me?

No, the MMR vaccine protects has been exhaustively studied and proven safe.

Does the MMR vaccine cause autism?

No. Numerous epidemiological studies have found no association between the MMR vaccine and autism.

How long after vaccination does it take to build protection?

After receiving the MMR vaccine, your body takes time to create antibodies, which is what provides you protection if you are exposed to the virus in the future. As with most vaccines, it takes about two weeks to build up to full protection.

I got measles vaccinations as a kid. Am I covered for life?

Most but not all people vaccinated against measles are protected for life, and the chance of being protected increases with a second dose of measles vaccine. Those who develop a protective response to measles vaccine are thought to be covered for life as there is no evidence this protection is lost with age.

Adults who were vaccinated for measles between 1963 and 1968 should check their vaccination history to determine which vaccine they received. During that time, a version of the vaccine that used an inactivated form of the virus was available that was found to not be as effective and was ultimately withdrawn. Only about 600,000–900,000 people in the U.S. received that vaccine in the years it was available—a very small percentage of the current population.

How do I know if I’m protected against measles?

Your best bet is to check your vaccination records. If you don’t have access to your vaccination records and otherwise can’t recall whether you were vaccinated, the easiest thing to do is to get another dose. It is not harmful to get an additional dose of measles vaccine, even if you’ve been vaccinated previously or have natural immunity from prior infection.

Older adults who were born before 1957 are presumed to have naturally induced immunity, because they were likely exposed to measles before vaccines became available.

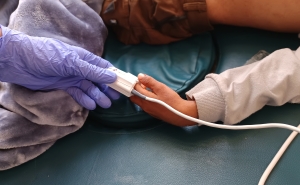

There are also blood tests that can measure antibodies to the measles virus. These tests are helpful for people who are immunocompromised or have another condition that prevents them from receiving the MMR vaccine. These tests are also common for ensuring health care workers are protected, especially those working in children’s wards or in areas with increased risk of measles exposure.

I’ve heard it’s better for children to get measles from another kid than to get a measles shot. Is that true?

No. Measles is a dangerous disease and the vaccine is very safe. The risks of severe illness, death, or lifelong complications from measles infection far outweigh the generally mild side effects some people experience following vaccination. Serious reactions to the MMR vaccine are rare.

Where can I get a measles shot?

You can get measles vaccinations at doctors’ offices, clinics, and government health centers. In communities where outbreaks are occurring, local health departments may also offer MMR vaccination clinics to help boost protection. Check with your local or state health department for more information.

How can I keep track of measles activity in my area?

The CDC website is a good resource for keeping track of national trends and outbreaks. State health departments, which report up to the CDC, are another great resource. In states where outbreaks are occurring, local and state health departments may provide more frequent updates to warn communities about outbreaks and recommend precautions or resources.

Where can I learn more about measles?

For more information, visit the CDC’s pages on measles and vaccination. You can also learn about the virus and its impacts globally from the WHO’s measles fact sheet.

Aliza Rosen is a digital content strategist in the Office of External Affairs at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Related:

More from the Bloomberg School

- See latest headlines

- Learn more about our departments: