Determining the Safety of COVID-19 Vaccines

While clinical trials are the gold standard to indicate if a vaccine’s benefits outweigh its risks, safety monitoring doesn’t stop there.

AN INTERVIEW WITH DANIEL SALMON

We’re hearing a lot about the effectiveness of potential vaccines. But I want to know more about the process where we determine how safe these vaccines are. I know these are going through rigorous clinical trials. But what can you learn from a clinical trial? And what don’t you learn from a clinical trial?

Clinical trials are really the gold standard. You randomize people into [groups who] either get the vaccine or not, and everything is blinded. The person doesn’t know whether they got the vaccine [or placebo], and the people running the studies don’t know that either. That randomization and blinding really help you draw valid conclusions from the data.

You start with small trials in phase 1. As you learn more—especially about safety, but also about immune response—you do larger trials. By the time you get to phase 3 trials—and for COVID vaccines, they’re pretty large—you have a really good indication that the benefits outweigh the risks for the population studied. That’s the process we’re going through now.

Ultimately, these results will go to FDA and their Vaccines and Related Biologic Products Advisory Committee, where all those data are reviewed by external scientists. It’s done in a public way, open to the public, so other scientists and clinicians and the public can see [that it works].

Even after the vaccine is approved for use, there are still things you don’t know. There are things that can happen that are uncommon, or that happen in subpopulations that are either not adequately studied or excluded from the trials, so you continue to look at the safety of the vaccines once they’re rolled out largely. It’s that post-licensure, or post-rollout, use safety assessment that really helps you make sure that the vaccines are, in fact, very safe.

How do we find out whether there are problems afterward?

There are a variety of ways. You have passive surveillance systems, which allow anybody to report anything. The one in the U.S. is called the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, which allows the public and clinicians to make reports. [These systems are] useful for identifying problems you didn’t anticipate. There’s a new system for COVID vaccines that the CDC is rolling out where it’s basically texting reports from early vaccinees.

We turn to large health care databases that keep track of who got what vaccine and what happens to them afterward to answer vaccine safety questions that might arise once a vaccine is rolled out.

This will be a huge undertaking. We’re talking about hundreds of millions of people getting this vaccine. How do you tease out what is just something that was going to happen to someone anyway, versus something that is the result of getting this new vaccination?

There’s always the potential for a real adverse reaction. In the case of COVID vaccines, these are new technologies. We have to be particularly careful and prudent. If there is a real adverse reaction, we have to figure that out quickly, we need to figure out how common it is, if it’s more common in some populations than others, and if possible, the biological mechanism for why that happens. Then, depending on how frequent it is, it might change vaccine recommendations. It could even change the authorization to use the vaccine, depending on how serious and how common it is.

Vaccine programs are prone to coincidental adverse events derailing them, especially in programs where you vaccinate a lot of people in a short amount of time. For example, if we vaccinate 10 million people over 65, we’re going to have heart attacks and strokes that occur in the same day as the vaccine, just by chance alone. If you take 10 million people today over 65, a lot of them will have heart attacks and strokes. The key is to quickly and rigorously—and with credibility—separate real adverse reactions from coincidental adverse events that happened around the time of vaccination.

We typically calculate the background rate of adverse events in [large health care system] databases prior to rolling out the vaccine. The Vaccine Safety Datalink is one such system. For heart attacks and strokes, it will calculate the rate of heart attacks and strokes in their population prior to rolling out the vaccine. And then when we start to see heart attacks after vaccination, we can compare that to the rate that would have occurred anyway.

There are people in this country who are very hesitant about getting vaccinated. How are we going to reassure people who are prone to this skepticism that there’s not a major problem?

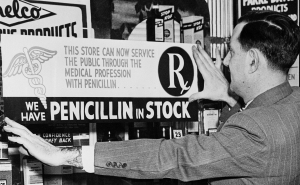

It’s a real challenge. In 2019, the World Health Organization declared vaccine hesitancy a top 10 global health threat. We were seeing reoccurring outbreaks of measles because there were communities where people were refusing vaccines. In fact, in 2019, we almost lost our measles elimination status in the U.S. because of some of outbreaks. We see vaccine coverage for diseases like HPV is quite poor, largely [due to] hesitancy, and influenza vaccine coverage every year is far lower than it should be. Part of it is that people are worried about the safety of vaccines, and part of it is they may not perceive the risk of disease to be as bad as it really is.

As this pandemic has evolved, there’s a huge mix in how the public sees the government response. There’s a substantial portion of the population that thinks COVID is not a big deal—that scientists and public health are making a bigger deal out of it than it really is.

We also see problems with things like compliance with wearing masks, and even people questioning the safety and effectiveness of mask wearing. At the same time, there’s a large segment of the population that feels like the government response has been totally inadequate, and that politics have undermined science. The credibility of organizations and public health authorities like the CDC and the FDA have also really gone down.

We see that about half the population doesn’t intend to get a COVID vaccine if made available free of charge— at least not right away. That’s really a problem because at the end of the day vaccines don’t save lives—vaccinations save lives. But if most of the population doesn’t want those vaccines—either because they don’t think [COVID is] a big deal or they’re worried about the safety of the vaccine—then our greatest tool will be ineffective.

During the 2009 H1N1 outbreak you were involved in overseeing some of the safety and effectiveness work on that vaccine. Can you tell us a little bit about how that worked and what lessons we need to take into account today?

At the time, I was the director of vaccine safety at the National Vaccine Program Office. I was responsible for overseeing the safety monitoring of the 2009 H1N1 vaccines. In that situation it really wasn’t a new vaccine, it was a strain change. In fact, if H1N1 had emerged six months earlier, it just would have been a part of our seasonal flu vaccine—and we know a lot about the safety of flu vaccines.

There was always some potential for a real adverse reaction we hadn’t anticipated, but we had a lot of confidence that the vaccines were very safe. What we were worried about were these coincidental adverse reactions derailing the program. So, what did we do? First, we got all hands on deck. We had clear leadership within the Department of Health and Human Services—from the secretary to the assistant secretary for health and the assistant secretary for preparedness and response. They really empowered me and my office to do our job.

We took all of these health care databases that we had the capacity to use—the CDC’s Vaccine Safety Datalink, data from Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense, Indian Health Service, Center for Medicaid Services—and we brought them all together. We also developed a new system called PRISM with Harvard Pilgrim [Health Care], where we linked 10 state immunization registries to four large health insurance companies. Ultimately, this gave us a tremendous amount of data. All of these data are anonymous and de-identified.

All this information was looked at by a federal immunization safety task force chaired by the assistant secretary for health and for preparedness and response [and] high-level scientific leadership from the NIH, FDA, CDC, and Departments of Defense, Veterans Affairs, Indian Health Services, for internal coordination. We also had an external advisory group called the H1N1 Vaccine Safety Risk Assessment Working Group as part of our National Vaccine Advisory Committee. These were independent experts that didn’t have a conflict of interest in terms of their funding and their research, and also independent from the program promoting the vaccine.

Every two weeks, the scientists within the government shared data, and then we would share this data with this advisory committee. Once a month they made public reports, so there was transparency. We had a very rigorous system. We had a lot of data and set it up in a way that it would be credible, so that if we saw a problem and we assessed the data and came to a conclusion, that the public would believe it.

Daniel Salmon, PhD ’03, MPH, is a professor of International Health. He is the director of the Institute for Vaccine Safety based in the Department of International Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

RELATED CONTENT

Public Health On Call

This interview is adapted from the December 4, 2020, episode of Public Health On Call.