The Visible and Unseen Dangers Lurking in Floodwater

Floodwater carries risks of injury, illness, and even death.

A vehicle is left abandoned in floodwater on a highway after Hurricane Beryl swept through the area on July 8, 2024, in Houston, Texas. Brandon Bell/Getty Images

Flooding is the most common and costly natural disaster in the U.S., and thanks to climate change, rising sea levels, wildfires, and changing precipitation patterns are increasing the number and intensity of extreme weather events with torrential rainfall. Already this year, there have been 39 flood-related deaths. Forecasters at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) are predicting “above-normal” hurricane activity this season, adding to the flooding risk.

Climate change is heating the oceans, too, and warmer-than-average ocean temperatures increase the amount of water that evaporates into the air, says Natalie Exum, PhD ’16, MS, assistant professor in Environmental Health and Engineering. When more moisture-laden air moves over land or converges into a storm system, it can produce more intense precipitation—such as heavier rain.

If the climate continues to warm, which most experts agree that it will, Exum says we will see even more flooding, and not only in the estuarine and coastal areas most at risk. Flood frequency in the U.S. is projected to more than triple by 2050 (relative to 2020) to reach an average of 45 to 85 flood days per year.

“I think [climate change] is closing in,” Exum warns. “The oceans are rising, the rivers are getting breached, and the heavy rains are making floodwaters rush.”

With the increasing intensity and frequency of extreme weather events, it’s important to recognize and prepare for both the visible and the unseen dangers associated with flooding:

An increased risk of drowning, which is the leading cause of death during flash floods and coastal floods. Even in shallow water, floodwater currents can be deadly. According to NOAA, just six inches of fast moving water can knock over an adult and 1–2 feet of water can carry away most cars. The CDC reports that the most common flood deaths occur when a vehicle is driven into hazardous floodwater.

Injury from dangerous objects. Lumber, vehicles, and other debris like glass can get swept up by rushing waters. Wild or stray animals can also be carried along by floodwater and may bite if alive or present disease risk if dead. And downed power lines can pose electrocution risk.

Exposure to household and industrial chemicals. Floodwater may contain hazardous household waste (e.g. bleach, antifreeze, weed killers, drain cleaners, and cleaning solutions), medical waste (soiled dressings, body parts, bodily fluids, pharmaceuticals, and medical devices) and industrial waste (paints, acids, bases, radioactive materials, heavy metal solutions, and wastewater with hydrocarbons) that can cause illness. When heavy rainfall hits an area that is experiencing drought, pollutants such as pesticides, automobile fluids, and fertilizers that have accumulated on the ground are flushed in high concentrations into the water.

Exposure to pathogens. Continuous, heavy rainfall can cause rivers to overflow and may overwhelm and damage water infrastructure like sewer and drainage systems, contaminating floodwater with animal and human waste.

“Any type of floodwater that has sewage in it is extremely pathogenic” Exum says. “The most immediate risk is gastrointestinal.” It's easy to get sick from exposure, she explains, adding that after a flood, the heavily inundated areas see more acute gastrointestinal illness (AGI)-related emergency room visits.

Contaminated drinking water. Water treatment plants are often located next to rivers, making water treatment and distribution systems particularly vulnerable when flooding occurs. Much of U.S. water infrastructure is aging, compounding the issue. Just two years ago, historic flooding in Jackson, Mississippi, damaged operations at a water treatment plant leaving more than 150,000 people without safe drinking water for weeks.

Public drinking water systems have safety mechanisms in place to alert the community if the water is safe to drink or not, but for those with private wells, “it’s much harder to know if your well is contaminated,” Exum says. It’s crucial to keep alert for boil-water notices, and to test water before resuming consumption.

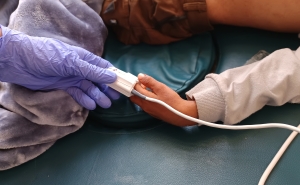

If contact with floodwater is unavoidable, minimizing exposure is key. “You don't want any type of open wound to be touching that water; that's a direct entry right into your body. When you do have contact with it, make sure that you're wearing the proper protective equipment—gloves, waders, and eye and face masks," Exum says.

If you do come into contact with floodwater, the CDC recommends that you:

- Wash the area with soap and clean water as soon as possible. If no soap or water are available, use alcohol-based wipes or sanitizer.

- Immediately seek medical attention for wounds.

- Wash clothes contaminated with flood or sewage water in hot water and detergent before reusing them.

Keep in mind that contamination and other hazards can linger even after the flood has receded. Standing water creates the perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes, which are vectors for a number of diseases. Animal carcasses may carry Salmonella and E. coli, and their decaying flesh may attract rats and other carrion-feeders. And some fungi, which flourish in dank, wet environments, may take root. “Microbes eventually die. You can disinfect them as you're cleaning up,” Exum says. “But when you've got a saturated house—it begins to grow mold.”

Morgan Coulson is an editorial associate in the Office of External Affairs at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.