Why COVID Surges in the Summer

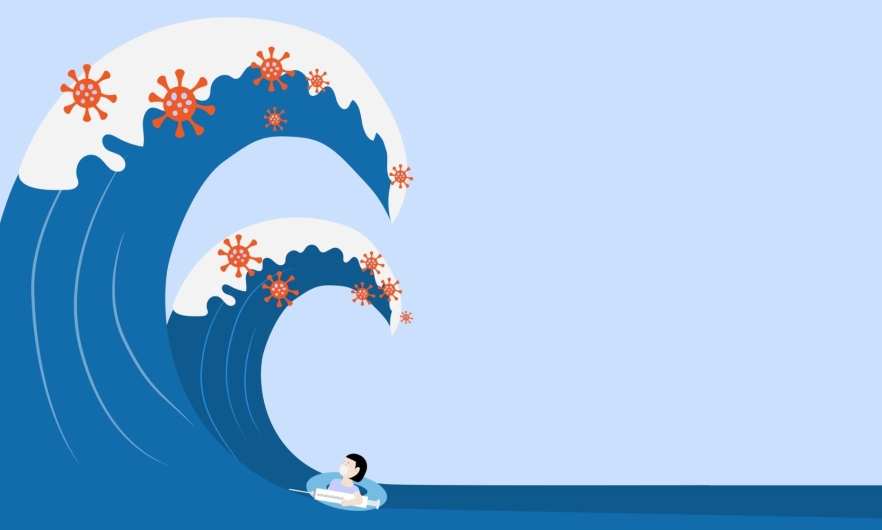

Hot weather, human behavior patterns, and an easily mutating virus create the perfect recipe for COVID’s peak in the summer.

Fall and winter are known as the time when respiratory viruses surge. When COVID emerged in 2020, it joined flu and RSV as one of the common respiratory viruses that peaks during the colder months. Since then, COVID has transitioned from pandemic to endemic, but has also maintained dual seasonality, peaking twice a year.

Every summer since 2020, COVID rates have risen in July and August, due to a confluence of virological, behavioral, and environmental factors. While it’s still too early to say whether this dual seasonality will peter out or become the norm, understanding why these summer surges happen can help us better protect against infection, severe disease, and ruined vacations.

Why do we see waves of COVID infections in the summer?

Several factors drive summer COVID waves. By mid-to-late summer, many people’s immunity—either from their last vaccination in the fall or from a previous infection—has waned considerably. That, combined with the emergence of more transmissible variants, makes the chance of infection more likely.

Human behavior also plays a major role. As the weather gets hot, we spend more time in air-conditioned indoor spaces, where most virus transmission occurs, explains Andy Pekosz, PhD, a professor in Molecular Microbiology and Immunology. With the windows closed to keep the cool air inside, we restrict ventilation and air circulation that has shown to reduce virus spread.

Many people travel more during the summer, with roughly half of Americans surveyed saying they planned to travel more, farther, and for longer in 2024 than the year prior. Travelers are not only exposed to more people—including from regions with more COVID cases—but also may be more likely to write off mild symptoms as simply the result of jet lag, not illness. Tiredness, headache, or a sore throat—all common after a long flight—are also symptoms of COVID, and without testing to be sure, a traveler may unknowingly expose others.

Pekosz experienced this himself after an international trip in July. At first he chalked up feeling tired to the massive time change, but when he started sneezing, he tested at home and it was positive. “I could have easily blown that off and just attributed everything to jet lag,” he says. “With a mildly symptomatic case, I may not have registered that it could be COVID and gone about my business for another couple of days while I was infectious.”

Why are there summer waves of COVID infections but not other respiratory illnesses like flu and RSV?

COVID’s ongoing dual seasonality can be attributed to both the higher presence of the virus year-round and its ability to mutate.

“The number of COVID cases that are present year-round is so much higher than we see for flu or RSV,” Pekosz explains. With that higher baseline, when conditions make for easier transmission—like increased travel and heat driving people indoors—there are more cases to fuel a larger wave of infections. “With flu or RSV, there are so few baseline cases during the summer that these changes in behavior don’t cause the same spread.”

Even when COVID rates are relatively low, more cases circulating year-round means more opportunities for the virus to mutate, which SARS-CoV-2 has proven to do very easily. When this happens, new variants emerge that are often more transmissible and better able to evade immunity. “The virus has shown itself to be very malleable, very able to handle mutations,” Pekosz says.

How might summer COVID waves impact our vaccination strategies?

The 2023-24 respiratory virus season marked a shift in COVID vaccination strategy in the U.S. to one of annual fall vaccination. That means that—just as with annual flu vaccines—governing bodies like the FDA and CDC use global surveillance data to predict which strains will be circulating and recommend a corresponding vaccine formulation. This happens in the spring so that manufacturers can prepare a vaccine for distribution in early fall.

But when infection rates increase, so do the chances for the virus to mutate. A wave of infections in the summer could result in new dominant variants that the vaccine may not protect against as effectively.

We saw this evolution play out in real time earlier this year. The FDA’s vaccine advisory panel was scheduled to meet in mid-May to make their recommendations for the fall, but they postponed the meeting to early June to allow more time to monitor the FLiRT variants that had recently become dominant in the U.S. On June 6, the FDA recommended monovalent JN.1-lineage vaccines, and then a week later updated their recommendations to a preference for the KP.2 strain, a member of the JN.1 family of variants.

“From a public health perspective, it would be great if we could send the same ‘go get your vaccines before respiratory season’ message at one time of year, with the updated vaccines timed to be available then,” Pekosz says. But consistent summer COVID waves could impact those recommendations. “It may end up that some individuals, particularly high risk individuals, are going to be urged to get vaccinated in early summer ahead of a presumed summer wave,” he says.

However, it’s unlikely that the upcoming season’s updated vaccines would be available by then, and those individuals would only have access to the previous season’s formulation. The previous season’s formulation would still provide some protection against severe disease and hospitalization, but it likely would have reduced effectiveness against newer variants.

Will COVID ever become seasonal like flu and RSV?

While the U.S. has experienced a wave of COVID cases every summer since 2020, it’s too early to say whether this is a long-term trend. Many public health experts still expect the virus’s annual spread will eventually look more like those of flu and RSV, which tend to peak during the winter. But exactly how long it will take to settle into that seasonal pattern is not clear.

“Historically, there are examples of viruses that do settle into a seasonal pattern after a transition period,” Pekosz says, pointing to the 1918 influenza pandemic, which he says took five or six years to take on the seasonal pattern we’ve come to expect. “We've got to hope that it'll settle into a more seasonal pattern, but we should also start thinking about strategies to deal with it if it doesn't.”

Can we expect COVID cases to drop before they rise again in the winter?

According to the CDC’s wastewater surveillance, COVID activity is high or very high in many states, with levels in the South and West nearing what they were in January. As students and teachers head back to school over the next few weeks, Pekosz expects cases will continue to spread before the fall vaccine formulation is rolled out.

While infection-induced immunity comes with higher risks than vaccine-induced immunity, this late summer wave will offer good population-level protection that will allow for case rates to trend back down. “I expect we’ll see a little bit of a lull starting around the middle of September or so, before we start seeing the late winter surge of COVID cases,” Pekosz says.

Aliza Rosen is a digital content strategist in the Office of External Affairs at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.