Project Development

This section includes resources to assist you with getting started on your project. This includes identifying what the problem is that you’re planning to tackle, what your proposed innovation is, and what your project objectives are. There are also resources on using journey mapping to identify what point(s) along the WIC journey your intervention will impact, how to use WIC MIS data to target interventions, how to develop a project logic model, what organizations you should plan to partner with, and how to develop a project workplan.

Project Development Resources

Before You Start Your Project

This section discusses the necessary first steps of planning for and developing your project. It includes problem or need recognition, identification of potential solutions, and developing project objectives. If you are considering developing and implementing an innovative project, there are a number of questions that you must first ask yourself and your team.

What is the problem?

Challenges in service delivery or desired outcomes can be identified by staff in a WIC local or state agency. They are often the first to perceive that there are situations that need to be changed or problems that need to be solved so that services can be provided in the most effective, efficient, caring, and respectful manner possible. Staff work daily with participants and are often witnesses to clinic or agency operations that could negatively affect the way that services are delivered. They may additionally engage in conversation with clients that could provide insight into client perception of clinic operation. Challenges in service delivery or desired outcomes (for example, participant retention) may also be initially identified by local WIC leadership or programmatic and administrative staff. This problem identification is often based on focusing on participant information collected for service delivery and analysis of this information (i.e., data). Problems may also be referred to as needs.

Staff problem identification may therefore be the first step of project development and problem solving. The second step is to substantiate your problem identification. This step will require preliminary data collection and analysis. Beginning to substantiate problem identification can be a straightforward activity. For example, you could talk with other staff to gain their perspectives and/or conduct a participant satisfaction survey. However, problems with service delivery and outcomes must always be confirmed by data examination and analysis by the program (or clinic) administering agency.

Do you have an idea?

As discussed above, problems or situations may be identified by staff. Staff may very well have thoughts about how to rectify the problem. Again, this is possible because staff work directly with clients, carry out clinic activities, and collect information. Local WIC leadership are also in the position to utilize their knowledge and experiences to develop projects to address and potentially solve the problem. Communication is the key to determining if your idea is likely to address the problem. You could start with your colleagues, go next to your clinic supervisor or leadership and follow the protocol in place to reach out to the upper (e.g., state) management. If the state agency has both recognized that there is a problem (by data analysis) and supports your idea, you can begin to think about how to carry out the project.

What are your project objectives?

Your project is being developed to address a problem and your goal is to “fix” it. Goals are generally broad – e.g., improve retention. Objectives are the activities and steps that you must complete to achieve your goals. Objectives convey the short-term outcomes that you anticipate will be accomplished by implementing the project. By articulating your objectives, you are clearly identifying the outcomes that you believe will be achieved by carrying out your project, which will ultimately achieve your goal. The best objectives are S.M.A.R.T.:

Specific: Know what it is you will do, who will do it, and who will be the audience.

Measurable: Know how you will measure the impact of the objective.

Achievable: Given the circumstances, resources, time, etc., objectives must be attainable.

Relevant: Objectives must align with the overall project goal. Will achieving the objective contribute to achieving the overall goal?

Time-bound: Objectives should be achievable and measurable within a specific and realistic timeframe. This timeframe needs to be stated in the objective.

An example of a research goal is: To determine if increased signage outside of WIC clinics increases WIC enrollment in that clinic (this example is for illustrative purposes only and any similarity to planned, ongoing or completed projects is coincidental and not intentional).

Here are two examples of SMART objectives associated with this goal:

- The project coordinator will recruit 40 current WIC participants from 5 WIC clinics to participate in 5 focus groups by July 1, 2023.

- The survey consultant will carry out 5 focus groups of 8 WIC participants each to determine how they perceive current external WIC signage between July 15, 2023, and August 15, 2023.

Photo source: https://cires.colorado.edu/outreach/evaluation/evaluation-101

Using WIC Management Information System (MIS) Data for Project Development

Whenever you work with clients, you probably use your agency’s automated Management Information System (MIS) to input participant data; determine their Program eligibility; determine nutritional risk; guide nutrition and breastfeeding education and referrals to health and social services; assign food packages; document understanding and agreement of their Rights and Responsibilities, issue benefits, and schedule appointments.

In addition to being a repository for participant information, an agency’s MIS is a valuable tool for your project in that it houses data that can be used for project planning and implementation, identification and targeting of clients who are at risk for early exit, monitoring and tracking, and project evaluation. MIS data can be used to identify those at risk for early exit by examining those who do not recertify by participant category, participant characteristics such as race/ethnicity, primary language and geographic location.

MIS data

Examples of MIS data that may be relevant to your project are below. However, not all MIS include the following data. Additionally, your agency’s MIS may contain data not listed below.

Participant descriptive data:

- Demographics

- WIC category

- Total number of WIC enrolled members in the household

- Participation in TANF, Medicaid, SNAP

- Maternal parity

- Breastfeeding status and history

- High risk status

- Foster care

WIC Program data:

- Family participation over time

- Certification/recertification dates

- Series of appointment types

- Appointments kept

- Benefit issuance date

- Benefit redemption

- Benefit expiration

Accessing MIS data

By working with the organizations and individuals who will assist you with project evaluation, you will have identified the data that you require for participant tracking and project evaluation. You will now need to determine if you will be able to access the data. While individual agency staff do have access to some MIS data, it is limited access and often in aggregate form. In order to utilize MIS data, your state agency must first give you permission to use it and indicate to you if the data that you plan on requesting is available. Once you have permission to utilize data, you will need to submit a data request. The process by which local agencies request data from the state agencies will vary, so first ascertain your state’s process. It is critical that you include detailed descriptions of the data, variable names, and time period that you are requesting. If you are not specific, your request may not garner the data that you require. Participant names and/or ID numbers are not to be requested, as they will not be provided to ensure participant anonymity. Please see the section later in the toolkit, Using MIS Data to evaluate impacts of an innovation on participation and retention: Requesting data and creating database, under Evaluation, for more information.

The state WIC office will review your request and inform you of its availability. Some states will provide data formatted to your specifications, while others will provide data according to their standard formatting. It’s important to understand that the primary responsibility of the agency’s data unit is for program administration and providing data for individual project data requests may be delayed.

When the request has been fulfilled, work with your data/evaluation partner to ensure that you have received the data that you requested and that it is complete. You may need to provide additional descriptions and requests to obtain the data you need.

How to Develop a Logic Model

A logic model is a way to graphically represent the project’s “theory of change”. According to the UN, a theory of change is “a method that explains how a given intervention, or set of interventions, are expected to lead to a specific development change, drawing on a causal analysis based on available evidence”.1 Underlying a logic model is a series of ‘if-then’ relationships that express the program’s theory of change.

Program Logic Models

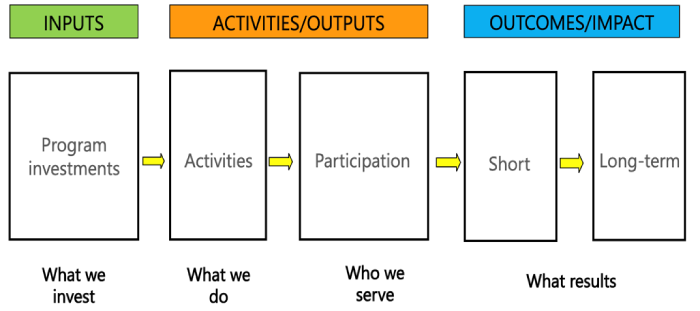

In WIC, you will likely use what is known as a Program Logic Model. The five components of a Program Logic Model are:

- Inputs: the resources invested in a program (i.e., technical assistance, a new software, staffing)

- Activities (processes): the actual events or actions done by the program and its staff to achieve program’s objectives

- Outputs: direct products of program activities (often measured in countable terms)

- Short-term Outcomes: the set of short-term or immediate results at the population level that are hoped to be achieved by the program’s activities

- Long-term Outcomes: the anticipated long-term results of the program (i.e., changes in health status, such as morbidity, mortality, etc.)

See below for what a basic Program Logic Model looks like:

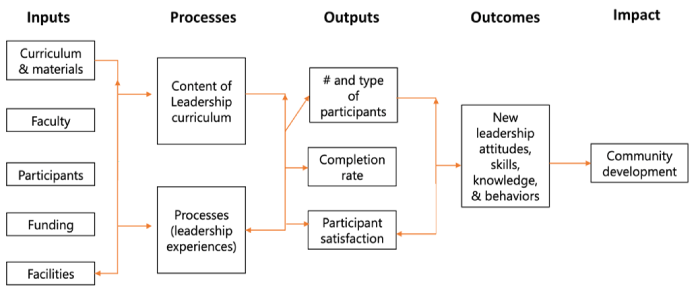

Below is an example of a Program Logic Model for a community development program run out of a university.

Outputs vs. Outcomes

Outputs are the products of the specific activities (at the program level). For example, the number of nutritionists who attended an education session is an output. Some additional examples of outputs include:

- The number of staff trained

- Proportion of clinics with breastfeeding materials in waiting rooms

- Percentage of caregivers/parents/guardians who can recall a nutrition education message

- Percentage of participants who were satisfied with their services

Outcomes, on the other hand, are the state of the target population or the social condition that a program is trying to change (at the population level). For example, the percentage of participants who redeemed their benefits in last month is an outcome.

You can see a graphic relationship between outputs and outcomes below:

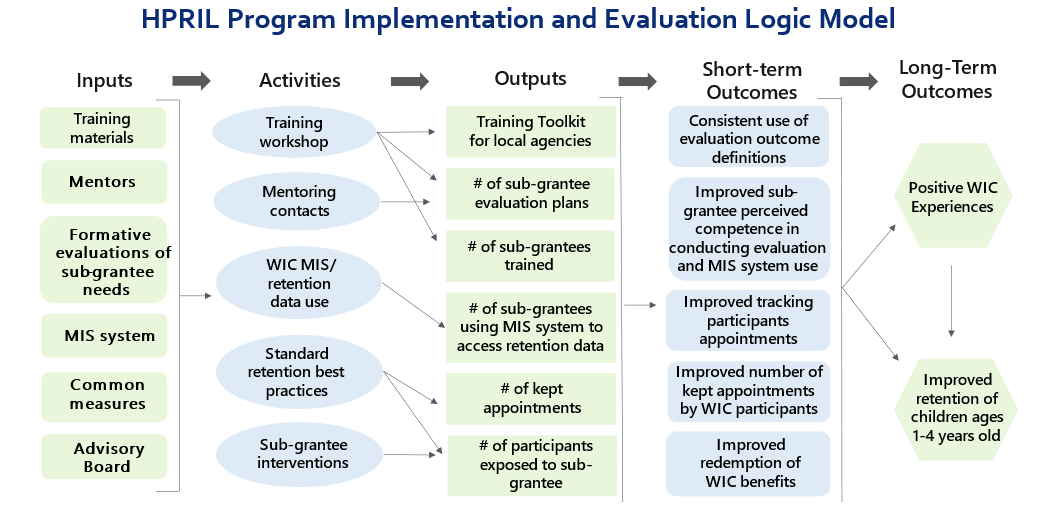

Below is the logic model for HPRIL’s program implementation and evaluation, which includes the project inputs, activities, outputs, short- and long-term outcomes.

Logic Model Template and Sample

Included in the resource guide is a logic model template for you to use. This includes spaces for you to insert your planned inputs, activities, outputs, short- and long-term outcomes, as well as contextual factors. As a reference, a sample logic model is also included from Pima County WIC for its HPRIL project. This will give you an idea of what should be included in each of the sections from the perspective of a local agency implementing an innovative project.

Reference

- United Nations Development Group (UNDG). UNDAF Companion Guidance: Theory of Change. https://unsdg.un.org/sites/default/files/UNDG-UNDAF-Companion-Pieces-7-Theory-of-Change.pdf.

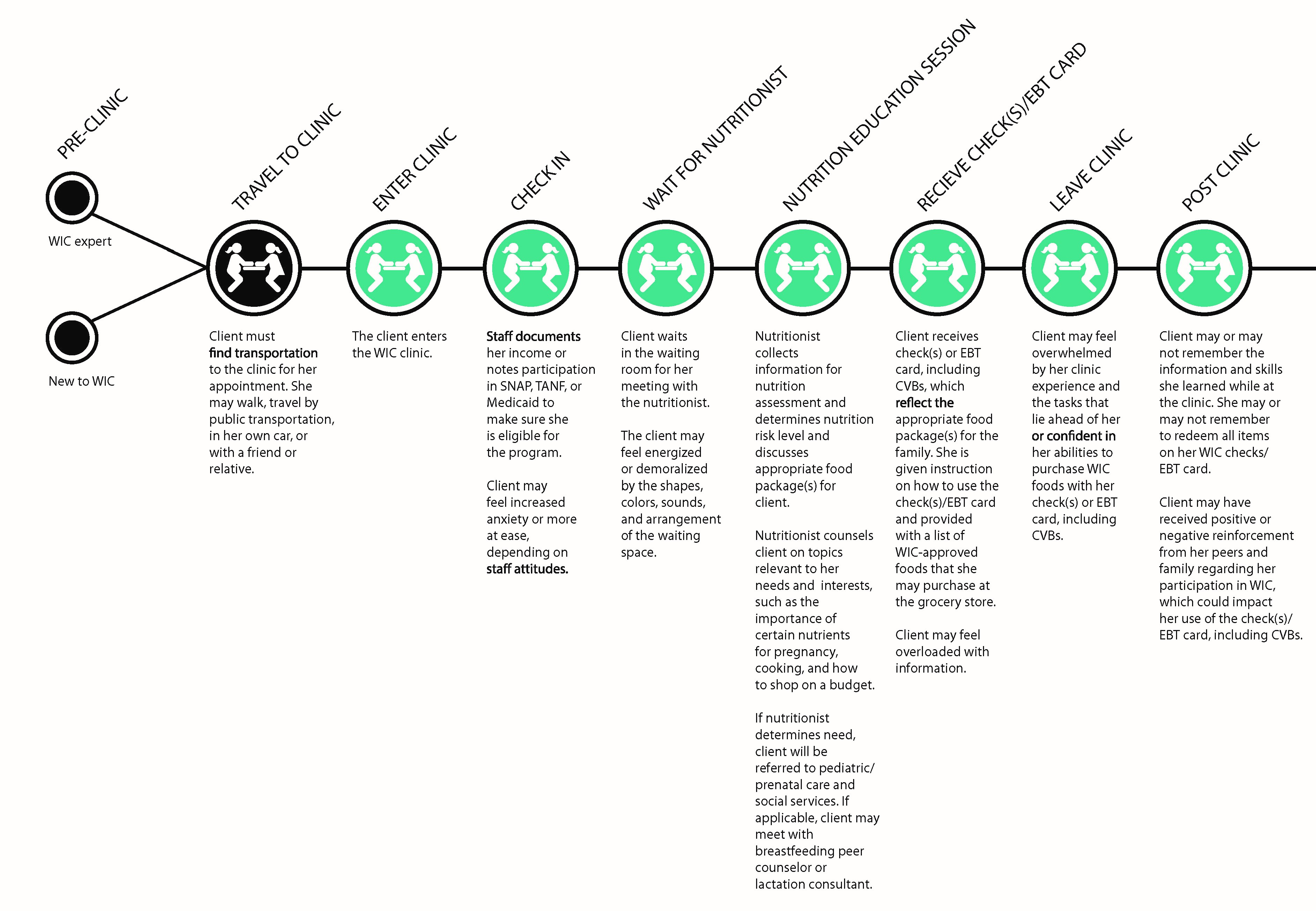

How to Use Journey Mapping to Explore Your Local Context and Shape Innovative Tool Implementation

Design thinking is a problem-solving approach that balances logic, intuition and emotion and provides human-centered solutions. Recent applications to social contexts include health care service delivery.

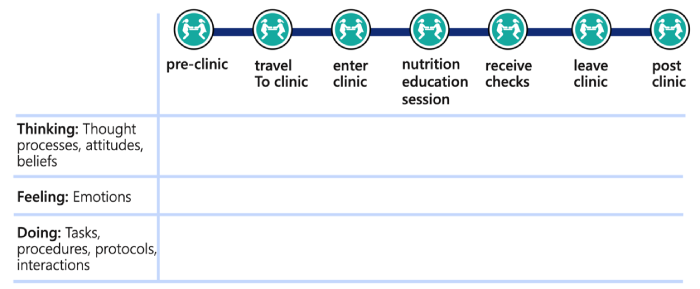

A journey map is a design thinking method. It is a visual timeline of micro-interactions (otherwise known as touch points) during an experience with a product or a service. It is generally from one point-of-view and demonstrates positive and negative moments throughout the experience that promote or hinder a desired behavioral outcome.

Below is an example of a journey map of a portion of a WIC participant’s experience and includes space to note what a participant is thinking, feeling, and doing at each point along the WIC journey.

How can Journey Maps help you?

- Foster empathy with the experiences of your clients and colleagues.

- Help you to understand the nuances of the multifaceted WIC client and WIC staff experiences in your clinic.

- Create a framework for making comparisons between programs/organizations/clinics and for organizing and sharing innovations.

- Plan projects that address the identified challenges.

- Help you think about the nuances of successful project implementation and about what is important to measure during the client and staff journey to know if you implemented your project as intended and achieved your goals.

Creating your journey map:

Below are the steps in the process of creating a journey map:

- Determine the scope. Whose experiences do you want to show in your journey map? Are they the current WIC clients? Current WIC staff?

- Decide what information you will use to inform your journey map. Information such as MIS data, customer satisfaction data, local program wisdom or other data can be utilized.

- The WIC journey is long, and it is important to determine start and end points.

- Decide what the touchpoints are between the two defined end points. Each touch point is a specific interaction between the person who is completing the journey and a task or other person(s).

- Fill in the details. What is the person thinking, feeling and doing? Flesh out the detailed experiences of clients and staff at each touch point with answers to these questions.

- Note which parts of the journey are positive and which are challenging. At this point you will have completed your project journey map.

A sample journey map from the National WIC Association (2013).

Source: https://s3.amazonaws.com/aws.upl/nwica.org/wic_journey_map.pdf.

Using a journey map

Here are considerations for implementing your innovative tool based on your journey map:

- Note if/how you think the innovative tool will change what clients and staff are thinking, feeling, or doing at each touch point.

- Think about how the anticipated changes at different touch points will impact the trainings and protocols to be developed, data collection and analysis, etc.

Journey Map Template

This journey map template provides an example of different touch points in the WIC participant journey and includes space to note what a participant is thinking, feeling, and doing at each point along the WIC journey.

Who are Your Partners?

Finding and partnering with organizations, groups and agencies is critical to effectively implementing, carrying out, and evaluating your project. Among other activities, partnering with appropriate organizations can facilitate developing and implementing your project, accessing a population of interest, developing and disseminating targeted project materials, project evaluation, and dissemination of findings. Here is a non-exhaustive list of potential partners and examples of the functions and benefits of each partnership. It is likely that you already have productive linkages and working relationships with these types of organizations.

- Health care agencies

- May assist in population access and material distribution

- Local health departments

- May assist with project integration with ongoing health department efforts

- Public schools

- May assist in linking with community residents

- Social service agencies

- May provide information to understand your population characteristics and needs

- Other non-profit organizations serving the community of interest (e.g., libraries, community organizations, groups serving non-native speakers)

- May provide population “expertise”, credibility

- Foundations, associations and coalitions

- May provide funding, means of disseminating results

- Institutions of higher learning (colleges or universities)

- May write grants and provide expertise (e.g., project development, data analysis, evaluation)

Linkages with government funding agencies may also represent a partnership (e.g., through a cooperative agreement), but may be strictly a business relationship.

How do you partner with appropriate organizations?

As noted, your organization may have existing linkages with organizations that could play a role in developing, implementing, and evaluating your project. Expanding the roles of these organizations may increase their involvement in your project. However, your organization may not have pre-existing relationships with some organizations that you deem to be instrumental to project success. Regardless of the current involvement, following the steps below will assist in establishing, expanding and fostering partnerships.

- Research potential organizations that are likely candidates and their potential roles. Make sure that the organization has a similar mission as yours.

- Identify appropriate individuals within the organization to contact

- Be able to comfortably communicate the “problem” and your ideas about how to rectify it, and explain project protocol if at least partially developed

- Explain their organization’s potential role and solicit their feedback

- Once agreed upon, develop a timeline and, if necessary, a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) or contract, and execute them

- Establish communication processes and frequency, accountability, and (as appropriate) deliverables

- etermine what organizational requirements must be completed prior to project implementation (e.g., Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval)

These steps may not be appropriate for establishing linkages with all potential partners that you have identified as tentative partners (for example, potential funders). Universities are well-suited to write proposals and may be the first potential partner that you contact.

Photo source: https://www.ceislermedia.com/single-post/2019/03/12/coalition-building-the-power-of-people

Developing a Workplan

When planning your project timeline, it’s important to develop a workplan to map out activities, target dates, who will be assigned to each activity, and outputs associated with each activity. As a reminder, local agencies must receive state agency approval for new workplans and protocols. This HPRIL workplan template can serve as a guide for how to organize a project workplan. We have also included some sample activities you might include as well as potential milestones to consider. This template is divided into three phases: Planning, Implementation, and Evaluation.