How Dangerous is Dengue?

With global warming and ever-increasing travel, the disease is spreading around the world.

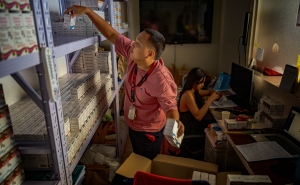

On March 25, Puerto Rico’s health secretary declared an epidemic after cases of dengue began to surge dramatically across the island. The U.S. territory, home to 3.2 million people, has reported at least 549 cases of the mosquito-borne infection so far this year, compared with a total of 1,293 cases for all of 2023.

Anna Durbin, MD, director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Immunization Research and professor in International Health, says she wasn’t surprised. “We're seeing outbreaks in all regions of the world. Dengue is very cyclical. Depending on where you are, we see a bad outbreak every three to four years.”

Dengue is endemic in over 127 countries, and almost half of the world’s population, about 4 billion people, live in areas with a risk of infection. Last year, more than 5 million cases were reported worldwide, according to the WHO.

In this Q&A, Durbin explains the dynamics of dengue infection, who is at greatest risk, and whether it might reach the continental U.S.

What are the symptoms of dengue?

About 75% of people who are infected with dengue have what we call subclinical symptoms, meaning they may have a fever for a day or so and feel achy, but not sick enough to seek medical care. But about 25% of people have much more severe symptoms. They have a high fever, no appetite, severe achiness, and a very low platelet count, which can result in bleeding. Around 5% of people infected with dengue have very severe illness that results in what we call plasma leakage, meaning they can't maintain their blood pressure, and can go into shock. Those are the cases we really worry about.

Who is at the greatest risk of severe infection?

The reason we see health care systems overrun during a dengue outbreak is that we can't predict who's going to develop that very severe form of dengue. We tend to hospitalize a lot of people, mostly to monitor them, and try to prevent them from going on to that stage.

We know that you're more likely to have a severe infection with your second dengue infection, but we also know that doesn't happen to everybody. It's still only a small percentage of those second infections that cause more severe disease.

How many times can a person become infected with dengue?

There are four different kinds of dengue, and we think that when you've been infected with one type of dengue, you have very long-lived if not lifelong immunity to symptomatic or severe disease with that serotype. You can be infected with each of the four serotypes, but your chances of having more severe dengue with your third or fourth infection is quite low.

Can it be deadly?

It can be, although physicians in dengue-endemic areas will tell you that with proper management, nobody should die from dengue if they present [for clinical care] in time.

Fluid resuscitation—replacing lost bodily fluids—is what's key to preventing death, but it has to be done in a careful way. Your blood pressure starts to go down because the plasma in your veins has leaked out. We give fluids to help keep that blood pressure up. But just as fast as that plasma leakage happens, it can reverse. You need really experienced people who know how to treat dengue properly. And if treated properly, the mortality rate is very low, about 0.2%.

I always say that if I got dengue, I wouldn't want to be in a U.S. hospital. I would want to be in Ho Chi Minh City or Bangkok. Because we don't see dengue the way people in Vietnam and Thailand do.

Is there a vaccine?

There are two vaccines, Dengvaxia and Qdenga, but they aren't available to everyone.

Dengvaxia is only approved in the U.S. for kids ages 6 to 16 who have already had dengue. It requires three injections to be given over the course of a year. You also must have a blood test to show that you already had dengue, which can increase the cost.

The second vaccine, Qdenga, requires two doses, three months apart. Right now, the WHO is recommending that Qdenga be used in people ages 6 and older in places where there's a lot of dengue circulating. It won’t be available in the U.S. or Puerto Rico for the foreseeable future, because the company that developed the vaccine, Takeda, withdrew its application to the FDA.

There is another vaccine—a single-dose vaccine—that was developed by the NIH and that we tested at Hopkins. The NIH licensed that vaccine technology to many different manufacturers, including the Instituto Butantan in Brazil. They just published their efficacy results, which look very good. But again, it's not available in the U.S.

Where is dengue most prevalent?

All tropical and subtropical regions of the world. With global warming and world travel we're seeing it spread all over the world. We're now seeing cases in areas where we hadn't seen them before, such as Southern France.

Are you anticipating any dengue outbreaks in the continental U.S.? If so, where would that happen?

I would expect to see it in Florida and Texas, predominantly. We regularly see cases along the Texas-Mexico border. But an outbreak is possible in any of the tropical areas of the U.S. I don't think we'll see huge outbreaks in the continental U.S. the way we've seen in other parts of the world. But we'll certainly see locally acquired cases every year.

We don't see dengue spread quite so much in the continental U.S. because we have so much air conditioning—people don't have windows open. If they do, they generally have screens on those windows which prevent the mosquitoes from entering the house.

What are some misconceptions about dengue?

One big misconception is that it can spread from person to person. It can't—you need a mosquito. If you're with someone who has dengue, that person can’t give it to you directly.

Number two is, if you've had dengue, you won't get it again. You can get it again, and it can be worse depending on how many infections you've had.

Three is that you can only get it in underdeveloped countries. You can get it anywhere the mosquito lives and dengue is circulating. You should be aware—especially if you're traveling—that it's present in all the tropical and subtropical regions of the world.

The other thing to note is that it can take about two weeks to become symptomatic.

What are the treatments for dengue?

Generally, it's rest and fluids. You can also take Tylenol, but you want to be careful about how much you take, because dengue can sometimes have an effect on the liver, as can acetaminophen. We recommend that you do not take non-steroidal anti-inflammatories like ibuprofen or aspirin as they can affect platelet count.

How do I avoid contracting dengue?

It's hard to think about mosquito protection every time you go outside, but you should be protecting yourself using mosquito repellents containing DEET and wearing long sleeves and pants.

Morgan Coulson is an editorial associate in the Office of External Affairs at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.