How Drug Shortages Are Affecting Cancer Treatments

Clinicians are facing a new hurdle in their patients’ cancer treatment: a shortage of chemotherapy drugs.

The U.S. is facing shortages of more than a dozen cancer drugs, as well as hundreds of other medications, including antibiotics. The shortfall has impacted hundreds of thousands of patients.

Like many clinicians, gynecological oncologist Amanda Nickles Fader has had to adjust the way she delivers treatment as the mainstays chemotherapy have become scarce.

In this Q&A, adapted from the July 7 episode of Public Health On Call, Joshua Sharfstein, MD, speaks with Fader, MD, an associate professor in Gynecology and Obstetrics at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center, and Mariana Socal, MD, PhD '17, a drug supply chain policy researcher and an associate scientist in Health Policy and Management, about the far-reaching impacts of nationwide drug shortages and how they’re affecting patient care.

Why have you turned your attention to drug shortages?

ANF: We've made so many treatment advances in the last decade that are extending survival and improving quality of life for patients with cancer. Chemotherapy drugs are among the most important medicines we use, and they’re one of the most important tools I have as an oncologist to help my patients.

However, we're currently facing a significant shortage of these essential medicines to help treat our patients. In the U.S. right now, we have a shortage of 15 indispensable chemotherapy drugs. We think over 90% of hospital systems across the country now are impacted by this shortage.

How is a patient’s treatment affected when a drug is in shortage?

ANF: The drugs in most significant shortage are among the most utilized drugs to treat the vast majority of cancers. These are curative intent treatments, meaning that when we use these treatments, either alone or in combination with other novel therapies, a number of patients have a significant chance of cure.

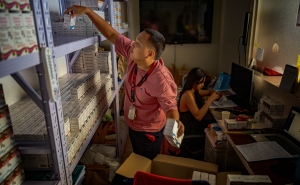

Shortage can mean different things for different institutions. It can mean that an institution or hospital is completely out of a drug, or that we're running low on supplies. In that latter instance, we have to be responsible in terms of how we use the drug supply that we have. Sometimes that means using practices at the pharmacy level, to preserve every last drop of chemotherapy and make sure that none of it goes wasted. We've sometimes had to make some adjustments in terms of the dosing or the interval of the drugs, or we might switch a patient to a drug that is in the same class and works just as well as the drug that's in shortage, but perhaps it has a higher side effect profile, or it takes longer to administer, so the patient has to spend more time in the hospital to get the treatment. These are still very effective ways of delivering these drugs, but it will help us preserve those drugs longer.

There are certainly some trade-offs there, but for other diseases and for other cancers, there may not be a good alternative drug to substitute if one of those critical drugs is in shortage.

Why are so many cancer drugs and other medications in short supply?

MS: Unfortunately, drug shortages have become part of the day-to-day operations in many of our hospital systems, across many specialties. They have been a problem in our health care system for several years.

I think what's happening today with these chemotherapy agents is that there have been manufacturing problems in certain plants. Sometimes even one drug manufacturer having a problem can disrupt the entire market for that drug.

What's behind these manufacturing problems?

MS: Generic drugs, which are not protected by a patent, may be produced by many different manufacturers competing in the same market. Generic drugs are also typically cheaper than drugs that are under patent. These cheap products have been historically more vulnerable to manufacturing problems.

If you have four or five different companies that manufacture the same product, they compete for price, and each of them is continuously trying to offer lower prices for their drugs. There is no incentive for these companies to invest in improvements in manufacturing practices, like new machinery or renovations for their facilities. As a result, every so often you hear about a facility having [production] problems.

Which drugs are more likely to be in shortage?

ANF: The older school, cytotoxic chemotherapy drugs that are now primarily generic formulations are in shortage. They remain among the most critical drugs we use. They are part of that chemotherapy backbone that we build upon and add new therapies to. Some of them have been around for more than two or three decades but remain some of the most highly effective drugs that we use to treat cancer.

What can be done to rectify the situation?

MS: It is important to remember that there's a chain of events happening behind the scenes that ultimately results in the drug being available or not on the pharmacy shelf or in the hospital's inventory. This drug supply chain typically starts far away from the U.S.

For example, to produce a generic drug, there is a key component called the active pharmaceutical ingredient—the chemical part that exerts the clinical effect on patients. Our research has found that over 85% of all of the active ingredients needed to produce generic drugs for the U.S. are produced overseas. These ingredients are then transported to a second player—the facility that will then manufacture the finalized product.

Multiple steps in this supply chain are prone to quality problems, not only in manufacturing the finalized product, but sometimes all the way back to manufacturing the active substances.

It is also very important which products we are purchasing. Are we purchasing the products manufactured with better quality practices? We have no way to know.

Are you hopeful this issue will be resolved?

ANF: We’re starting to see some improvement in the short term. The FDA is actively working with manufacturers to expand production of the drugs by expediting review of new manufacturing facilities. It's approving importation of some of these drugs from overseas to help bolster the supply.

But other than the companies coming back online and producing the drugs we need, I'm not confident right now that we have a good long-term strategy. This is just a Band-Aid. And I'm worried for my patients that this could keep happening and could potentially worsen with each shortage, given what we're seeing now. It's vital that we see long-term strategies enacted, with oncologists like me and patient advocates at the table to help with those solutions.

Joshua Sharfstein, MD, is the vice dean for Public Health Practice and Community Engagement and a professor in Health Policy and Management at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. He is also the director of the Bloomberg American Health Initiative and a host of the Public Health On Call podcast.