WTO TRIPS Waiver for COVID-19 Vaccines

Sharing the know-how behind making COVID-19 vaccines is key to scaling up production and addressing emerging variants.

A Q&A WITH ANTHONY D. SO, MD, MPA

The Biden administration announced it would seek a “TRIPS waiver” of intellectual property protections related to COVID vaccines.

In this Q&A, Anthony D. So, MD, MPA, a professor of the practice in International Health, explains the waiver and what it could mean for COVID-19 vaccines.

What’s the TRIPS waiver for COVID vaccines all about?

The TRIPS waiver refers to a proposal, advanced by the governments of South Africa and India, to the World Trade Organization to waive intellectual property rights protection for technologies needed to prevent, contain, or treat COVID-19 “until widespread vaccination is in place globally, and the majority of the world’s population has developed immunity.”

In 1995, when the World Trade Organization came into existence, those signing up as members agreed that in exchange for the lowering of barriers to trade, they would abide by the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, or TRIPS.

This Agreement, pushed by knowledge-based economies like the United States and the multinational, research-intensive pharmaceutical industry, imposed a base of protections for intellectual property rights, from patents to copyrights. Before this was negotiated, more than 50 countries did not recognize patent protection on pharmaceutical products. The TRIPS Agreement changed that, and after a transition period of 10 years, ratcheted up these requirements on all but the least developed countries.

Middle-income countries like India came into compliance by 2005. The TRIPS waiver just seeks to temporarily suspend these protections until the pandemic has ended, so the world can better access the knowledge needed to combat the worst pandemic in a century.

What’s the rationale behind waiving intellectual property protections for COVID vaccines?

Sharing the know-how behind making COVID-19 vaccines is key to not only scaling up production, but also bringing forward the second generation of vaccines we will need to address emerging variants.

No single vaccine manufacturer can produce enough vaccines to cover the globe, and demand has far outstripped supply, with high-income countries taking the lion’s share of reserved doses. Proponents of a TRIPS waiver wonder how it can be right for a multinational vaccine manufacturer to hold exclusive rights that can stop other firms from stepping up to meet the need for vaccines, particularly in markets not being served by current vaccine producers. They argue that the public already has paid once or twice for such innovation, either upfront in research and development (R&D) costs or through purchase guarantees of these products, or both.

Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine—one of two now in use based on an mRNA platform—was paid for largely by the U.S. government, and in fact, Moderna has pledged not to enforce its patents related to the COVID-19 vaccine during the pandemic. However, making the Moderna vaccine likely involves other companies’ patented equipment and processes as well, so waiving patent protections on one piece of the process may not help other companies make the entire “recipe.”

This is why a TRIPS waiver is considered important to ensure other vaccine manufacturers would have the freedom to operate. It should also be acknowledged that a TRIPS waiver may accelerate scaling up some COVID-19 vaccines where untapped capacity for vaccine production still exists, and it may also encourage existing vaccine producers to step up their technology transfer efforts.

By noting its willingness to move forward with text-based negotiations over a TRIPS waiver at the World Trade Organization, the United States signaled a seismic shift in policy. However, it is only the beginning of a process.

Who is opposing the TRIPS waiver and why?

Other high-income countries, from EU countries and the United Kingdom to Japan and Australia, have yet to join the United States in supporting negotiations for a TRIPS waiver. Multinational pharmaceutical companies have vocally opposed the waiver, and disclosure forms from the first quarter of 2021 reveal that over 100 lobbyists had been enlisted to oppose the TRIPS waiver.

The main arguments boil down to protecting the incentive for future pharmaceutical innovation. The idea is that companies will be reluctant to invest in new technology if they feel that they cannot reap full financial benefit from their successes.

Yet before COVID-19 hit, R&D for pandemic vaccines was largely neglected by the private sector, and public financing understandably had to support this work. Many of the first COVID-19 vaccines that came to market relied on tax dollars to enable their effective development.

One of the key aspects of producing successful COVID-19 vaccines has been the process of stabilizing the COVID-19 spike protein. This innovation relied largely on public funding, and all of the vaccines currently on the U.S. market rely on this technology. But although they all benefited from publicly funded intellectual property, no vaccine company has stepped forward to join a global effort to voluntarily share its know-how through the COVID-19 Technology Access Pool (C-TAP), launched by WHO with the support of Costa Rica and 40 member state cosponsors.

Another question raised by opponents of the waiver is: Have companies been able to make a strong return on their investment? The answer appears to be yes. In a market almost entirely created by public sector purchase of vaccines for a pandemic, Pfizer brought in $3.5 billion in COVID-19 vaccine revenues in the first quarter of this year, with estimated profit margins in the high 20% range, by far its greatest revenue generator. Pfizer’s partner, BioNTech, received upfront public financing, both from the German government and the European Investment Bank, while Pfizer itself has secured 6 billion dollars thus far from the U.S. government in guaranteed purchases of its COVID-19 vaccine. So even if the TRIPS waiver were to enable other vaccine producers to meet the huge unmet demand, it is hard to argue that the public sector has not already provided multibillion-dollar incentives to bring forward needed innovation.

The pharmaceutical industry has also argued that the TRIPS waiver will not speed the scale-up of COVID-19 vaccines. This argument reflects the fact that the production process is very complex and difficult to develop without extensive support from existing manufacturers.

This may be particularly true for mRNA technology. While mRNA vaccine candidates are emerging in India and China as well, the intellectual property landscape for mRNA vaccines is highly fragmented, with a handful of pharmaceutical companies holding half of these patent applications. The TRIPS waiver would clear the path for these firms to move forward, as they enter clinical testing, without concern over conflicting patent claims that may not be resolved at pandemic speed.

Unlike Pfizer and Moderna, which make mRNA vaccines, AstraZeneca/Oxford has struck many more technology transfer agreements with vaccine producers in low- and middle-income countries for its vaccine based on adenovirus vector technology, which is easier to produce and distribute. Its vaccine price of $3 per dose is also less than half that of Pfizer/BioNTech’s vaccine in the African Union.

With first-generation vaccine producers already focused on booster doses to take on variants affecting high-income countries, will they be as focused when a variant spreads through lower-income country markets that largely remain unvaccinated? Two-thirds of the WTO’s members support the TRIPS waiver because they are unsure that their COVID-19 public health needs will be met by upholding patent protections as usual. Perhaps this reflects the experience of these countries’ governments in securing access to Pfizer/BioNTech vaccines, let alone the building blocks of knowledge to develop second-generation vaccines. Pfizer has been asking governments to put sovereign assets—such as federal bank reserves, embassy buildings, or military bases—as a guarantee against indemnifying the cost of future legal cases.

What else, beyond resolving intellectual property issues, is necessary to scale up vaccine production?

These negotiations over a TRIPS waiver will not take place overnight, nor will scaling up the technology transfer and ramping up the manufacture of COVID-19 vaccines.

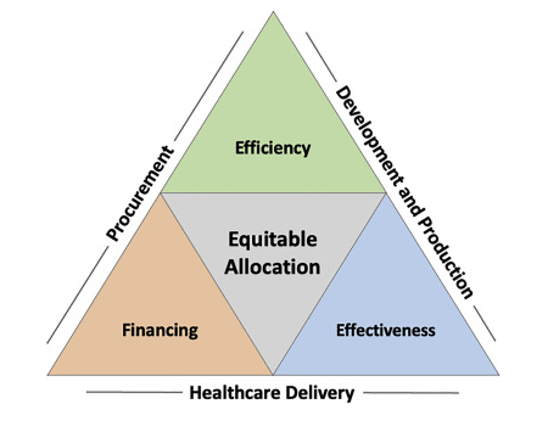

In a perspective piece for Cell’s new translational science journal, we recently discussed the complex issues involved in scaling up vaccine production and, importantly, ensuring that these vaccines make their way not only to high-income countries, but also more equitably to those in need across the globe. This will involve, among other things:

- Public investment in technology transfer

- Contracting of existing and new manufacturing facilities

- Sourcing other inputs like glass vials

- Pooled procurement facilities, from UNICEF to the Pan American Health Organization’s Revolving Fund for Vaccine Access, to buy and deliver the vaccines effectively.

We will also need to prioritize scaling up second-generation vaccines that have been adapted to address emerging variants or that are better suited for delivery where ultra-cold chains do not exist.

Source: So AD, Woo J. Achieving path-dependent equity for global COVID-19 vaccine allocation. Med 2021; 2(4): P373-377. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medj.2021.03.004

What are the next steps?

For years to come, we will need COVID-19 vaccines. A sustainable and affordable pipeline—one that will deliver in a timely way to all in need, not just to those in wealthy countries—must be put in place.

In the best-case scenario, a TRIPS waiver for sharing COVID-19-related knowledge and technology can lay an important foundation to an innovation ecosystem that ensures a fairer path out of the pandemic than we took going into the pandemic.

But no one doubts that there is a tough road ahead in negotiating the text to this waiver and in all the work that follows so that it might make an effective difference. Other questions will naturally arise, including the approach to intellectual property for tests and treatments for COVID-19, as well as the sharing of key research findings and data.

In the near term, the U.S. should also commit to sharing-and-exchange mechanisms for COVID-19 vaccines, especially as uptake of vaccines slows.

We had proposed a temporal trade, for example, on the U.S.-reserved doses of the not-yet-approved AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine with countries waiting and ready to use this vaccine now. By just swapping our line in the queue, vaccine doses may reach those in desperate need sooner. More such arrangements will be needed, particularly since AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine supplies globally have since been disrupted with the unfolding COVID-19 resurgence in India, from where much of its manufacture had been sourced.

In the meantime, the world must not lose any time in scaling up the public sector investment in the rest of the supply chain, from manufacturing to logistical delivery of these vaccines. The U.S. can lead a coalition of the willing to build upon and extend the use of such vaccine platforms through technology transfer. History will remember what is done to meet this moment.

Anthony So, MD, MPA, is a professor of the practice in International Health and the founding director of the Innovation+Design Enabling Access (IDEA) Initiative.