Enhancing Public Trust and Health with COVID-19 Vaccination

Why “If We Build It/They Will Come” May Not Apply to Humans and Vaccines and What Can Be Done About It

A Q&A with Monica Schoch-Spana (co-chair) and Lois Privor Dumm (member) of the Working Group on Readying Populations for COVID-19 Vaccine.

While the world anxiously awaits a COVID-19 vaccine, there are significant considerations to be made in terms of how to actually vaccinate a global population. Chief among them will be building trust and understanding to address concerns about the vaccine itself—especially one produced on an accelerated timeline.

To help advance the U.S. public’s understanding of, access to, and acceptance of vaccines that protect against COVID-19, a working group convened by the Center for Health Security with members from the International Vaccine Access Center and the Institute for Vaccine Safety, has released a resource, The Public’s Role in COVID-19 Vaccination: Planning Recommendations Informed by Design Thinking and the Social, Behavioral, and Communication Sciences. The resource provides recommendations for a people-centric approach to improve the planning and implementation of the COVID-19 vaccination program.

Monica Schoch-Spana of the Center for Health Security and Lois Privor Dumm of the International Vaccine Access Center break down some of the key points of the resource in this Q&A.

Q&A

Who should use this resource?

SCHOCH-SPANA: The report’s intended users are the sponsors, planners, and implementers of the COVID-19 vaccination campaign. This includes those involved in SARS-CoV-2 vaccine development, allocation, deployment, and communication. The Working Group envisioned this collective to be broadly inclusive: the federally led private/public partnership (Operation Warp Speed) charged with developing and disseminating a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine; the funders of vaccine research that can lead to clinically successful and socially acceptable products; local and state public health officials strategizing around vaccine delivery and population uptake; social/behavioral researchers with insights into vaccination-related human factors; and non-traditional entities new to public health’s vaccination mission including grassroots organizations who are able to provide hyper-localized understanding of vaccine access and acceptance issues in their communities and to serve as trusted vaccination champions.

What are the key recommendations in the report? What actions should be taken and by whom?

SCHOCH-SPANA: Vaccines represent a promising bioscientific solution to the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet, their widespread acceptance is also needed, and this is a social challenge, not a technical one.

The report recommends six steps to facilitate broad public uptake of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines:

- Put people at the center of a revolutionary SARS-CoV-2 vaccine enterprise. U.S. research requires reconfiguring to value the contributions of both bioscience and social and behavioral science to inform SARS-CoV-2 vaccine development. Joined by private foundations, the federal government should commit a portion of its budget and work through the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to support rapid response research into the social, behavioral, and communication issues related to COVID-19 vaccination, practically informing a rollout.

- Understand and inform public expectations about vaccine benefits, risks, and supply. Much is still unknown about what the diverse U.S. public knows, believes, feels, cares about, hopes, and fears in relation to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, and how that may change over time. The CDC, with the support of Congress, should fund state and local health departments, via the Public Health Emergency Preparedness grants, to form partnerships with grassroots-level organizations, practitioners, and other stakeholders to engage early and often with communities around COVID-19 vaccination.

- Earn the public’s confidence that vaccine allocation and availability are evenhanded. The currently charged social climate in the U.S. necessitates, more than ever, both a fair vaccination campaign and widespread public recognition of its fairness. The U.S. government should publicly pledge that everyone who wants a COVID-19 vaccine will get a COVID vaccine. Moreover, with stakeholder and public feedback, the CDC should reassess its pandemic vaccine allocation and targeting strategy, to boost public confidence that allocation decision making is neither capricious nor unjustly weighted in favor of other people.

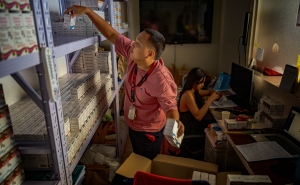

- Make vaccination available in safe, familiar, and convenient places. Making vaccines widely available and accessible will entail public health authorities preparing to meet communities—and, particularly, vulnerable populations—where they are. CDC and state and local health officials should develop vaccine delivery approaches that involve nontraditional partners and that incorporate locations that are easy to access and also feel safe to medically and socially vulnerable groups.

- Communicate in meaningful, relevant, and personal terms, crowding out misinformation. A profusion of true and false information now circulates around the COVID-19 pandemic, making it hard to sort health information and confirm its veracity. At the same time, scientific facts do not motivate a majority of people to act. To enable a successful COVID-19 vaccination promotion campaign, the U.S. government should sponsor rapid efforts for public-stakeholder engagement, formative research, and message development.

- Establish independent representative bodies to instill public ownership of the vaccination program. Governance structures for the U.S. COVID-19 vaccination program that incorporate public oversight and community involvement have the potential to inspire greater public confidence in, and a sense of ownership over, the public health intervention. Each state should establish a public oversight committee to review and report on COVID-19 vaccination systems, ensuring that allocation is fair, that target groups receive the vaccine, and underserved populations disproportionately affected during the pandemic are justly attended.

How far in advance of a COVID-19 vaccine release should officials be thinking about these things? What would we need to know to start instilling public trust now?

SCHOCH-SPANA: With the current lag time in vaccine availability, U.S. vaccination planners and implementers can exercise foresight and take proactive steps now to overcome potential hurdles to vaccine uptake.

We need to know how people think about SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, where they fit in their lives, what value they add, what holds people back from being vaccinated, and what practical measures could diminish potential barriers to vaccination.

What are some of the biggest concerns about public acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine?

PRIVOR DUMM: When it comes to public acceptance, we want to ensure that all who are eligible can get the vaccine, including high-risk populations, front-line and essential workers, and the young and healthy that transmit the disease to others.

To do that, we need to ensure that there is a safe and effective vaccine and enough doses to give to everyone that needs it; that people see the value of being vaccinated; that they trust those who are providing the vaccine; and they have a way to get it.

Each one of these goals is crucial to public acceptance. First, we don’t know what type of efficacy and safety a vaccine will have and whether it is appropriate for all populations. Particularly in older populations or those with severe underlying illnesses, the vaccine may not work as well and other strategies will be needed.

Second, there will likely be insufficient quantities to give to everyone initially and the public will need to trust the authorities who decide who gets it first. Explaining the rationale for allocations will be a challenge. Convincing the people most at risk that they should get the vaccine may be another challenge if the vaccine doesn’t work as well as we hope, if people don’t trust the safety of the vaccine or the government or system that has perhaps let them down in the past. Younger adults or otherwise healthy people may not see the need for a vaccine and we will need to ask them to do something they might not otherwise do to help others.

Finally, accessing the vaccine may also be a challenge for some. They may have work or family responsibilities that don’t enable them to take time off to be vaccinated—possibly twice if it requires 2 doses—or have other reasons that make it difficult to access vaccination services such as lack of transportation, perceptions about costs, their family members or the community are also suspicious of the vaccine, fear of deportation, being treated poorly, or other types of discrimination.

What are some potential barriers to universal vaccinations in the U.S.?

PRIVOR DUMM: First, we need to ensure that there is a vaccine that is appropriate for all populations and that there is sufficient quantity. Assuming that the vaccine is in sufficient quantities and at an affordable price, experts and policy makers would need to consider whether the vaccine is recommended for everyone or just certain populations. If the vaccine is less effective in some populations (e.g, older adults) or prevents severe disease but not transmission, it may not be recommended for everyone

Additionally, there needs to be political will at national, state, and local levels to ensure that immunization is provided without taking away from other essential services. COVID-19 and vaccines have been quite politicized, so getting politicians, the community, businesses, health providers and advocates all on board will be key to making sure universal immunization happens. There may be debate over whether there vaccines are required and this is something that will need to be resolved at a state or local level. Anti-vaccine activists and disinformation campaigns are another concern as they stoke fear and misconceptions about the safety and value of vaccines.

Community acceptance will be a barrier if we don’t build trust and take the time and effort to understand the perceptions and concerns of a community. Messages about immunization and need to address why immunization is important for various populations with a diverse set of concerns, provide transparent information and set appropriate expectations. Some populations, particularly younger adults, may not see the need for vaccines and not access the system and those at higher risk may be concerned about getting immunized if there are large groups of people. Perceptions about safety have been voiced as a concern by a number of people.

Delivery of vaccines may be another challenge. The expected volume of vaccine needed is huge and the system may not be equipped in all parts of the country to safely store vaccines (and syringes) and administer a large number of doses over a short period of time. Some vaccines may require special storage conditions and new equipment may be needed. Non-traditional places for immunization may need to be added to ensure all communities have access to vaccines and they will need to track people and call them back if a second is needed (dependent on the vaccine).

What’s most important for people to keep in mind about a COVID-19 vaccine?

PRIVOR DUMM: Although early results are promising, we still don’t know what a vaccine will look like and how effective and safe it will be in certain populations. We will likely still need to be vigilant about washing our hands and isolating when testing positive or showing symptoms as no vaccine is 100% effective and certain people will still be susceptible. People should also get other vaccines including influenza or other recommended immunizations and should continue to take steps to prevent other health issues.

Preventing excess death, long hospital stays, and persistent effects that leave patients weakened and more susceptible to other diseases will help reduce hundreds of billions of dollars in direct medical cost due the pandemic alone, free up hundreds of millions of hospital beds that may be needed for other diseases, and help prevent the potentially catastrophic economic impact of long-term illness to families and society.

What are some of the unknowns?

PRIVOR DUMM: There are many things that we don’t know right now, including the efficacy and safety profile of the vaccine, the expected progression of the disease, whether the vaccine will need to be given every few months or every season to maintain levels of immunity.

There are a lot of investments being made to produce a vaccine or vaccines, but biologicals are historically unpredictable and we don’t yet know how a vaccine will perform, particularly in the most vulnerable populations or in controlling the spread of disease.

Predicting vaccine acceptance and ultimately our ability to control disease is also based on a very complex set of assumptions that are dependent on perceptions of disease and the value of vaccination, perceived risk to self and others, how knowledgeable and motivated we are given a set of cultural norms, how convenient it is to get the vaccine and how resilient we are to disinformation or other efforts to erode trust.

What can we be doing to address populations at highest risk of severe effects of COVID-19?

PRIVOR DUMM: We won’t be successful with immunization unless we reach our most vulnerable populations. There is a disproportionate impact of disease in communities of color and other vulnerable populations, yet according to recent surveys about intent to vaccinate, only about 25% of African Americans said they would get a COVID-19 vaccine.

There may be many reasons, but one reason given is concern about safety. While communications to allay fears about side effects can help increase acceptance, it is important to consider the drivers of decisions more holistically. There is rarely a single reason why a person does not get vaccinated and engaging the people that are in need of a solution is a smart way to go. Bringing together at risk populations, and the people that they interact with including businesses, health providers, government and others to co-create solutions can help build ownership and trust within a community.

Getting vaccines to new populations requires the same level of response as vaccine development and we must start figuring this out now.