How Will We Protect Afghans’ Health Under the Taliban?

Interview by Stephanie Desmon

After the Taliban was forced from power in 2001, Afghanistan saw an infusion of funding and support that led to dramatic progress in nutrition, maternal mortality rates, and other health indicators. With the Taliban’s return to power, international aid has dried up, and the country’s health care system has virtually collapsed.

Afghanistan native Nadia Akseer, PhD, MS, an assistant scientist in International Health at the Bloomberg School, now aims to bring together a network of Afghanistan-focused health researchers and health professionals from around the world to address the crisis. In this Q&A, adapted from the November 9 episode of Public Health On Call, Akseer talks about the country’s dire health care situation and why this time it’s necessary to work with the Taliban to protect Afghans’ health.

First, tell me a bit about the research you did for your dissertation, which I understand centered on what happened in Afghanistan when the Taliban came and went.

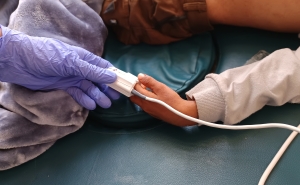

I studied maternal and child health and nutrition in Afghanistan and the progress the country had made since the first Taliban government ousting in 2001. When the U.S. occupied Afghanistan at that time, Afghanistan had some of the worst health indicators in the world. Maternal mortality was as high as 1,600 per 100,000 live births. Chronic childhood undernutrition was 60%, meaning that more than one in two children in the country were chronically malnourished. Many other indicators were abysmal as well.

When I started my PhD in 2011, 10 years had passed. Lots of money had been channeled into the country, so I wanted to see if there had been any gains. I studied many national datasets covering 2001 to 2015 and found that the country made dramatic progress. The maternal mortality rate I mentioned dropped by 75%, to 400 per 100,000 live births in 2015. Child and newborn mortality rates dropped by about 30%. Malnutrition had dropped from 60% to 40%. Access to health care services, such as antenatal care and delivering in health care facilities, had gone up from about 12% in the early 2000s to about 40% in 2015. Obviously rates of mortality and undernutrition were still poor, but the country had made progress.

What did you attribute those improvements to?

Improvements in maternal education and empowerment were a huge driver in almost all outcomes—nutrition, access to health care, reductions in maternal mortality. It was always the case that a woman going to school was a huge driver, with many different impacts on a woman’s and child’s health. Also, the deployment of health care workers such as midwives and nurses in the country was very important, resulting in direct gains of children’s and women’s lives being saved during delivery and various other outcomes as well. Although Afghanistan is still a universally poor country, they did make some improvements in reducing poverty.

I understand that you were born in Afghanistan and still have family and friends there.

Yes, my entire extended family still live in Afghanistan. My parents, my siblings, and I were able to leave in 1989, during the first Soviet invasion.

What have you learned about what's been going on since the Taliban recently came back to power?

Since the Taliban came back into power in August of this year, the country turned upside down almost instantly.

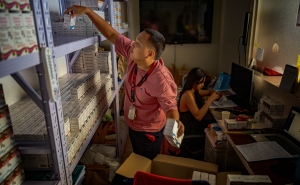

Long-term donors to Afghanistan, such as the World Bank, the IMF, and the European Union, who have been funding Afghanistan’s health care system for over 15 years, froze their funding immediately. There are about 3,500 health facilities in Afghanistan, and within a matter of weeks, 2,000 of them had shut down because there were no funds to keep the lights on, to pay health professionals, to buy supplies, such as essential vaccines.

Over 3 million doses of COVID vaccines have spoiled because no one is there to administer the cold storage. Women are not freely mobile at this point, which means there are very few female health workers—and in Afghan culture, a woman must provide care for a woman. Most girls are not going to school, and there are huge restrictions on those who can. There's a huge health care crisis and food insecurity crisis going on at the moment. And there are fears that the entire country is going to collapse within a matter of weeks.

Are there efforts afoot to try to help?

There are some limited efforts going on. Health care services in Afghanistan are provided predominantly by international NGOs such UNICEF or MSF, and also some local NGOs. Most NGOs have suspended activities because of a lack of funding, but some, such as MSF, have continued their activities there. It’s not nearly what's needed to keep that country safe.

What are you doing to try to make things right?

I think there are many different players in Afghanistan's health care story that have contributed to it, including the government, the NGOs, civil society, the diaspora, researchers such as myself, health care professionals who are there currently and also those who have fled. I think these stakeholders need to come together to use our skills, experience, assets, and networks to protect health in Afghanistan.

Within the Department of International Health, I'm leading a working group we're calling Mission Afghanistan 2030, to line up with the SDG goals. I'm hoping to bring these various stakeholders together to align on research, evaluation, and advocacy to support health in Afghanistan. I hope through this working group we can synergize our efforts and discuss joint funding opportunities, that we can build a network of Afghanistan-focused health researchers and health professionals from around the world, and really serve as a coordinating body for a common agenda.

Were you surprised at how quickly this fell apart?

Personally, I was not surprised. The Taliban are from the country, born, bred, and taught there. They know the culture and the country very well. The United States was there for 20 years and continued to fight off the Taliban all those years. It wasn't surprising to me that as soon as the U.S. left, the Taliban took over.

At this point, I would really push the entire world to think about this new government—and yes, they are the new government. That doesn't mean we should cooperate with them immediately and give them all this money, but we need to give them a chance and let them show what they can do to protect the civilians of Afghanistan. We really need to be there for them to support as needed.

Even though they created such a mess with the health care system before?

I believe that we have no choice. They are the government, and we need to be thinking about how we can protect the health of the 40 million Afghans in the country. We need to be careful how we approach it. We need to work with them in a way where they can gain our trust as an international community and collaborate with us on the country’s priorities.

I also feel that the Taliban there now is a different generation. It has been 20 years. Many of Afghanistan’s youth have grown up in this globalized world as well. They’re on social media. They are doing the things that youths and adolescents are doing all over the world. And they are now the frontline of the Taliban. This generation of Taliban may be more open to having a dialogue with the rest of the world on what we need to do to protect the health of the civilians in the country.

Stephanie Desmon is the co-host of the Public Health On Call podcast. She is the director of public relations and marketing for the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs, the largest center at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.