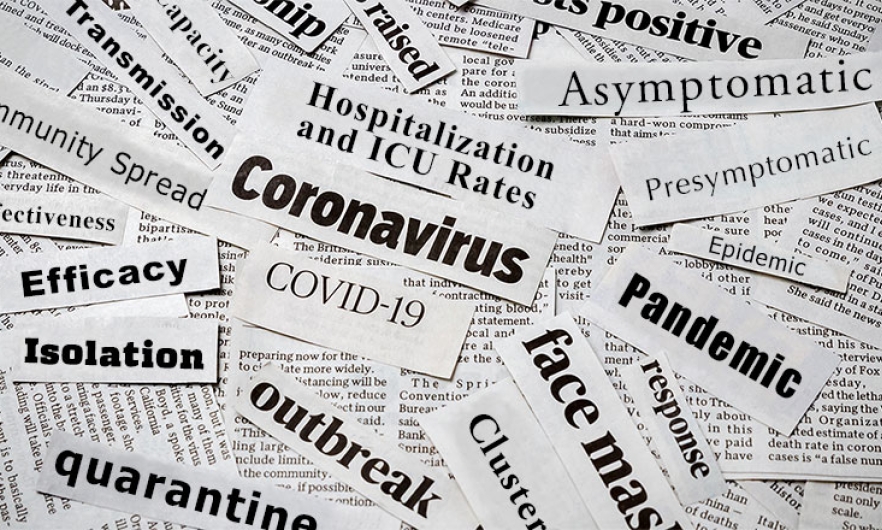

Clarifying COVID-19 Terminology

Efficacy vs. effectiveness, quarantine vs. isolation, and other often conflated terms in the COVID-19 lexicon.

This article has been reviewed by Rachel West, PhD and Gigi Gronvall, PhD of the Center for Health Security.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought a range of new terminology into everyday conversations. Some of these terms are often conflated, muddying the public's understanding of important concepts.

*Please note: Specific guidance is subject to change and is variable depending on vaccination/prior infection status, age, etc. For the most up-to-date information on COVID-19 please visit the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Here’s a breakdown of some commonly misused or misunderstood terms:

1.Efficacy vs. Effectiveness

These two terms are often used interchangeably in the context of the performance of COVID-19 vaccines in clinical trials. But there’s a key difference: Efficacy refers specifically to how a vaccine is performing in the trials. This is an ideal performance of the vaccine, as it is in a trial environment that can be more tightly controlled than everyday life.

Effectiveness refers more broadly to how the vaccine meets standards of success in the “real world,” after it has been released for consumer use. This gives a more realistic performance of a vaccine, and takes into account that in the real world, the vaccine may be offered in a range of primary care settings, and offered to a broader population of people, including those who may have health conditions or other factors which could affect how well the vaccine protects against disease.

SOURCE: NIH

2. Quarantine vs. Isolation

While quarantine has become somewhat synonymous with stay-at-home orders, both quarantine and isolation refer to actions taken once there has been a known exposure to COVID-19.

Quarantine “separates and restricts the movement of people who were exposed to a disease to see if they become sick.” In the case of COVID-19, this usually means that someone who is unvaccinated was in contact with a known COVID-19 case, but is not yet showing symptoms themselves. This individual will stay at home and away from others outside of their immediate household for 14 days following known exposure or risky behavior like travel.

Isolation “separates sick people with a contagious disease from people who are not sick.” In the case of COVID-19, isolation usually means that the individual has been diagnosed with COVID-19 and is staying away from others (isolating) so as not to infect them. Isolation tends to take place inside the home, where someone who has symptoms or has tested positive is isolated from other household members who have not.

Isolating separately is challenging, so if multiple people in a household have confirmed COVID-19, it’s fine for them to isolate together.

If one household member has COVID-19, that person should be isolated from others in the home.

SOURCE: HHS

3. Asymptomatic vs. Presymptomatic

COVID-19 can present with symptoms ranging from virtually none at all to serious illness requiring hospitalization. But there is a big difference between someone who has an asymptomatic case of COVID and someone who is presymptomatic—a distinction that tripped up the WHO back in June.

Asymptomatic individuals test positive for COVID-19 but “lack symptoms that would indicate SARS-CoV-2 infection.” Some people may not experience any symptoms during the entire course of their COVID-19 infection.

But some people may develop symptoms days after a positive test. These individuals would be classified as having been presymptomatic at the time of their positive test; they will eventually develop symptoms.

SOURCE: NIH

4. Epidemic vs. Pandemic vs. Endemic

The difference between an epidemic and a pandemic is one of degree: An epidemic occurs when there’s an increase in disease cases above normal in a limited population or area (for instance, a single country). An epidemic can become a pandemic if it spreads to several different countries or continents.

Separately, a disease is considered endemic if it is normally circulating within a certain population or geographic area. The flu is an endemic virus in the U.S., for example, and it’s suspected that even once vaccines are widely available, COVID-19 will become endemic as well.

SOURCE: CDC

5. Outbreak vs. Cluster

Epidemic and outbreak are two terms that can actually be used interchangeably for the most part, although an outbreak is usually used to define a specific, smaller geographic area.

Cluster, on the other hand, often refers to outbreaks on small and specific scales. A cluster would occur over a specific time period, within a defined location. For example, a heightened number of cases in a prison or long-term care facility may be referred to as a cluster.

SOURCE: CDC

6. Community Spread vs. Transmission

Transmission is technically used to describe the way in which the SARS-CoV-2 virus spreads from person to person. It’s typically used alongside words like contact or fomite, droplet, and airborne.

But community transmission and community spread are terms used interchangeably to describe what happens when there is significant disease spread in a certain population with no clear source. With COVID-19, high community transmission or spread complicates response efforts like contact tracing.

7. Death Rate vs. Mortality Rate

Death rate is a catch-all term that breaks down into two specific numbers: the case fatality rate and the mortality rate.

Case fatality rate, or CFR, is the specific number of people with confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 who die as a result of the disease. This is usually a very specific number, such as “out of 100 people diagnosed with COVID-19, 1 person dies.” The CFR is a proportion of deaths per total confirmed cases.

Mortality rate is a more general approximation of the number of deaths that occur within a larger population. This number might be something like “out of a population of 100,000 people, 10 people die from a specific disease.” The mortality rate is a number of fatal cases per a given population.

SOURCES: BBC, American Heart Association

8. Hospitalization and ICU Rates vs. Capacity

Hospital and intensive care unit capacity are statistics that describe the burden of COVID-19 disease in a particular community. These rates are usually expressed as a percentage: the number of occupied beds divided by the number of total beds.

Hospitalization rates, on the other hand, refer to the number of people in a specific area who are hospitalized after a diagnosis of COVID-19. The rate of those admitted is compared to the total population of a given area like a county, state, or country. It’s important to note, however, that hospital capacity is not just a matter of beds, but of staff available to care for patients.

9. Ventilator vs. Respirator

Ventilators and respirators are both in short supply, but they are not the same thing.

A ventilator, also known as a mechanical ventilator, is a machine usually used in a hospital setting that blows air through tubes into a patient’s airways.

A respirator, on the other hand, is a piece of personal protective equipment, or PPE, worn over the mouth and nose or face to prevent inhalation of airborne particles, gases, or vapors. N95 respirators are recommended for health care personnel in clinical settings but not for the average person because of a severe shortage of this equipment.

10. Positivity Rate vs. Prevalence

The positivity rate—also referred to as “percent positive rate” or “percent positive” is the percentage of all coronavirus tests performed that are actually positive. Positivity rate is usually expressed as a percentage. It is an indicator of whether enough testing is occuring, if enough asymptomatic and mild cases are being tested.

Prevalence, on the other hand, is a specific number of people who have (or had) COVID-19 during a specific time period. This would be the number of truly positive individuals out of the entire population—not just who is tested. Prevalence can help researchers and decision makers understand the larger picture of COVID-19 spread in a specific area or population.

SOURCES: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, NIH

Lindsay Smith Rogers is a content strategist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in the office of Communications and Marketing and producer of the Public Health On Call podcast.