Priority 4: Anticipate misleading rumors & potential loss of trust

Checklist to Build Trust, Improve Public Health Communication, and Anticipate Rumors During PHEs

Summary

❏ Activity 1: Enable appropriate understanding of what public health is and does

❏ Task 1.1: Establish what public health is and its benefits to society

❏ Task 1.2: Clarify how government services—including the public health department—are organized

❏ Task 1.3: Explain the goals and thought processes behind public health operations

❏ Task 1.4: Plan robust public feedback mechanisms prior to an emergency❏ Activity 2: Set expectations for public health response and communication at the start of a health emergency

❏ Task 2.1: Help members of the public understand issues of uncertainty

❏ Task 2.2: Establish processes and plans to communicate changes in guidance as understanding evolves

❏ Task 2.3: Set an appropriate communication cadence❏ Activity 3: Track, analyze, understand, and plan for anticipated rumors in local contexts

❏ Task 3.1: Establish tracking and analysis systems for social listening

❏ Task 3.2: Integrate an understanding of local audience values and needs with expected rumors

❏ Task 3.3: Develop prebunking and inoculation messages❏ Activity 4: Promote use of and access to trusted sources

❏ Task 4.1: Facilitate access to trustworthy health information and teach critical thinking skills to enhance information self-sufficiency

❏ Task 4.2: Enhance information accessibility and understandability

Misleading rumors undermine trust in public health. Lack of trust in public health reduces the effectiveness of public health communication. While Priority 1, Priority 2, and Priority 3 recommend enabling capacities and activities that build trust, and Priority 5 covers public health messaging and evaluation, this section describes how public health departments can anticipate and proactively mitigate common threats that diminish trust in public health, including misleading rumors. Table 1 provides a brief summary.

Table 1. Brief summary of common threats to trust in public health and how they may be addressed

| Anticipate… | Action… |

|---|---|

| People may not thoroughly understand what public health is or what public health departments do. | Engage in pre-emergency outreach that talks about the benefits and roles of public health. Provide easy ways for the public to seek information from public health departments before, during, and after emergencies. |

| PHEs may emerge rapidly and evolve over time, generating uncertainty. People and public health departments may seem to be on different pages, which could generate confusion—or even frustration—for everyone. | Provide structure to and transparency of public health communications early and throughout the emergency. Demand for information, interests, concerns, and emotional needs may fluctuate throughout the emergency, and public health guidance likely will shift in response.1 Communicating openly and honestly at a regular cadence will help lower the risk that the public views potential threats as abstract or has unclear expectations of emergency response guidance and countermeasures. |

| Misleading rumors will arise that undermines trust. | Establish processes to stay aware of circulating rumors. Consider ways to make the public more resilient to health rumors before they arise, including promoting access to and use of trusted sources. |

Activity 1: Enable appropriate understanding of what public health is and does

Public health—as a concept, an area of work, and a government service—suffers from a lack of shared understanding about its roles in and contributions to the community. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, some people may think of public health only in the context of a global health emergency or could hold negative views of public health because of certain response efforts.2-4 These negative perceptions and misunderstandings must be addressed to prevent the potential loss of trust during an emergency.2 This section reflects on how public health departments can leverage existing outreach efforts to educate people about what public health is and isn’t, how public health efforts benefit society, and how people can get in touch with their public health department—thereby hopefully mitigating losses in trust.

Task 1.1: Establish what public health is and its benefits to society

The first time people engage with public health should not be during an emergency.2-4 Regularly exposing the community to the valuable day-to-day work of public health departments can help build a baseline of awareness and mitigate distrust during public health events. Communicating about the diversity of public health activities—such as keeping people safe from drowning, making sure food is safe to eat, keeping water clean, and helping prevent chronic diseases—helps to increase public health’s visibility and show its valuable contributions to communities. This can be done through traditional, new, and community-driven communication channels. For example, creating public health-related stories, posts, and other content across health department social media platforms can build a following of community members, raise awareness, and promote trust in the “brand” of the public health department.2 Although these activities are often considered part of normal public health communication activities, health departments should prioritize them as a critical part of emergency preparedness.

Task 1.2: Clarify how government services—including the public health department—are organized

While it is important to share what public health does well, it is equally important to inform the community about those activities or decision-making capabilities that fall outside its scope, as well as how activities are organized within the health department. For example, if someone asks the HIV team about non-HIV services, public health staff should refer that person to a point of contact responsible for those specific services and explain why they cannot help, rather than simply declining to assist because the request falls outside their scope, as the latter could damage trust. Having a single community engagement team that cycles through all health department sections may aid in this effort. Investments in health and government literacy also can help the public better identify and utilize needed public health services, as well as build and maintain trust between health departments and communities.2

Task 1.3: Explain the goals and thought processes behind public health operations

Public health communicators should share their departments’ goals and processes in transparent and accessible ways. Highlighting goals such as keeping food safe, promoting healthy environments, and preventing disease outbreaks can help emphasize how community values are reflected in public health activities. Similarly, explaining decision-making processes can help to answer “how” and “why” questions related to public health actions. When the public understands how public health departments operate and their core goals, they are more likely to support public health activities during emergencies, even when those activities are challenging or burdensome.2

Some specific ways that public health departments can better share public health goals and processes include publicizing strategic planning processes and outcomes with members of the public; providing health boards and the public with descriptions of operations around specific health threats or topics; and ensuring that staff who regularly interact with the community, such as health inspectors, have written materials to explain how and why they are doing their work.

Task 1.4: Plan robust public feedback mechanisms prior to an emergency

Public health communication is not always immediately clear and comprehensive to the public. There may be additional questions, concerns, or needs for clarification. Providing opportunities for real-time dialogue between public health communicators and people, online or offline, as well as other speedy feedback mechanisms, is key to avoid confusion, frustration, or potential losses in trust. Examples include telephone hotlines staffed with public health employees who can answer questions, address concerns, or provide information; regularly monitored email inboxes and health department social media pages; and front desk personnel at the health department to welcome visitors and answer phones.2

In setting up robust communication mechanisms, it is important to avoid potential pitfalls. Failing to follow up on inquiries can lead to confusion and a reduced likelihood of informal secondary messengers sharing health department messages effectively. Failing to acknowledge feedback or lacking friendliness can lead to broken trust. Poorly monitored and maintained communication methods may do more harm than good if people feel ignored and discounted. Note that additional feedback mechanisms should be accessible to CBOs via other means, such as designated health department staff members acting as consistent points of contact for community partner feedback and needs.2

Furthermore, by monitoring these feedback points, health departments may be better able to evaluate the reach and effectiveness of their communication efforts. If capacity allows, daily monitoring of public feedback mechanisms can greatly improve the department’s responsiveness to community needs. Formal indexing and analysis of questions, comments, and concerns can help public health agencies better understand potential problem areas. Advisory committees, CBO leadership forums, or focus groups can help gather community sentiment and provide comments.2 See Priority 5 for more information on evaluating public health messaging.

Activity 2: Set expectations for public health response and communication at the start of a health emergency

Setting expectations at the start of a PHE can help ensure that the community is less surprised by emerging issues as they evolve. Clear expectations can help keep public health agencies accountable and, when met, preserve or increase levels of trust.

Task 2.1: Help members of the public understand issues of uncertainty

Emergencies are inherently uncertain events. As a PHE emerges, standard communication practices are to share what is known, unknown, and what is being done to fill those gaps.3 Describing any issues of uncertainty at the start of an event, as well as the scientific processes being undertaken that could help shed light on the situation, can help ensure public understanding and set appropriate expectations.5

While emergency communication can be relayed through social media-focused materials and appealing visuals, one of the most important channels to communicate uncertainty is through in-person briefings or recorded comments by health officials. Showing humility and relatability in stating “we don’t know” is a valuable source of empathy and connection. However, public health departments should consider the needs of intended audiences to determine the best ways to share information. In some situations, audiences may perceive officials’ lack of knowledge negatively, especially if they feel enough time has passed that answers should be available.2

Task 2.2: Establish processes and plans to communicate changes in guidance as understanding evolves

Along with sharing information about uncertainties, public health communicators should set expectations that while current guidance and approaches are based on the best available information, changes could and likely will occur as understanding about a PHE improves or the situation evolves.6 Developing processes and plans for how to communicate these changes in a timely and transparent way is important to maintain a rapport with the community.5 Public health officials should emphasize that any changes will be based on continuing analyses of the most up-to-date information.

Task 2.3: Set an appropriate communication cadence

In times of uncertainty and change, there is significant demand for new information and situational updates. When the public does not know when to expect updates, requests for new information can become more frequent and can leave voids that might be filled with rumors or incorrect information. By setting a predictable, appropriate, and clear communication cadence, public health communicators can help set expectations for when new information will be shared and preserve trust. The appropriate frequency of updates depends on the type and phase of emergency, health department capacities, intended audience, and communication channels. Additional communication opportunities may be inserted into the communication cadence if a specific need arises.2

Activity 3: Track, analyze, understand, and plan for anticipated rumors in local contexts

The spread of misleading rumors and deliberately false narratives is now an expected part of public health emergency events. Therefore, the public health community must anticipate these types of information and design processes to deal with them ahead of time. The project team has developed several other resources to assist in these efforts, including a framework for anticipating likely rumors during an emergency and the Practical Playbook for Addressing Health Rumors, which takes a hands-on approach to help public health communicators recognize and respond to health-related rumors.7,8

Task 3.1: Establish tracking and analysis systems for social listening

Public health communicators can better understand their information environments by tracking and analyzing online content, often referred to as “social listening.” They can use social listening tools such as Google Alerts and Talkwalker to manage information during an infodemic.9,10 They can also use informal methods, such as taking notes on questions asked at in-person events. Analysis of this information can be formal, like preparing a detailed insights report, or informal, like looking for common themes of rumors that arise.

Tracking and analyzing information at the community level can help improve understanding of issues specific to geography or culture that could require specialized intervention. Community health workers and public health nurses are well-positioned to help collect rumors and should have ways to share that information with public health communication teams.2 Additionally, public health departments should track rumors that were widespread during past health events, as these likely will re-emerge in future emergencies.

Task 3.2: Integrate an understanding of local audience values and needs with expected rumors

Understanding local audience needs, values, and priorities is a core component of everyday public health operations. This knowledge is critical to ensure appropriate and trusted communication during an emergency, which is why it is covered in-depth in Priority 1 and Priority 2. These factors should also be considered in the context of expected rumors that are likely to emerge during an emergency. Most rumors, misleading content, and purposefully manipulated narratives leverage strongly held beliefs and concerns,7 such as anxieties related to fertility, perspectives on the role of government, and worries about profiteering.11 Undertaking efforts to broaden understanding of local communities can help public health communicators anticipate and prepare for these types of rumors.8

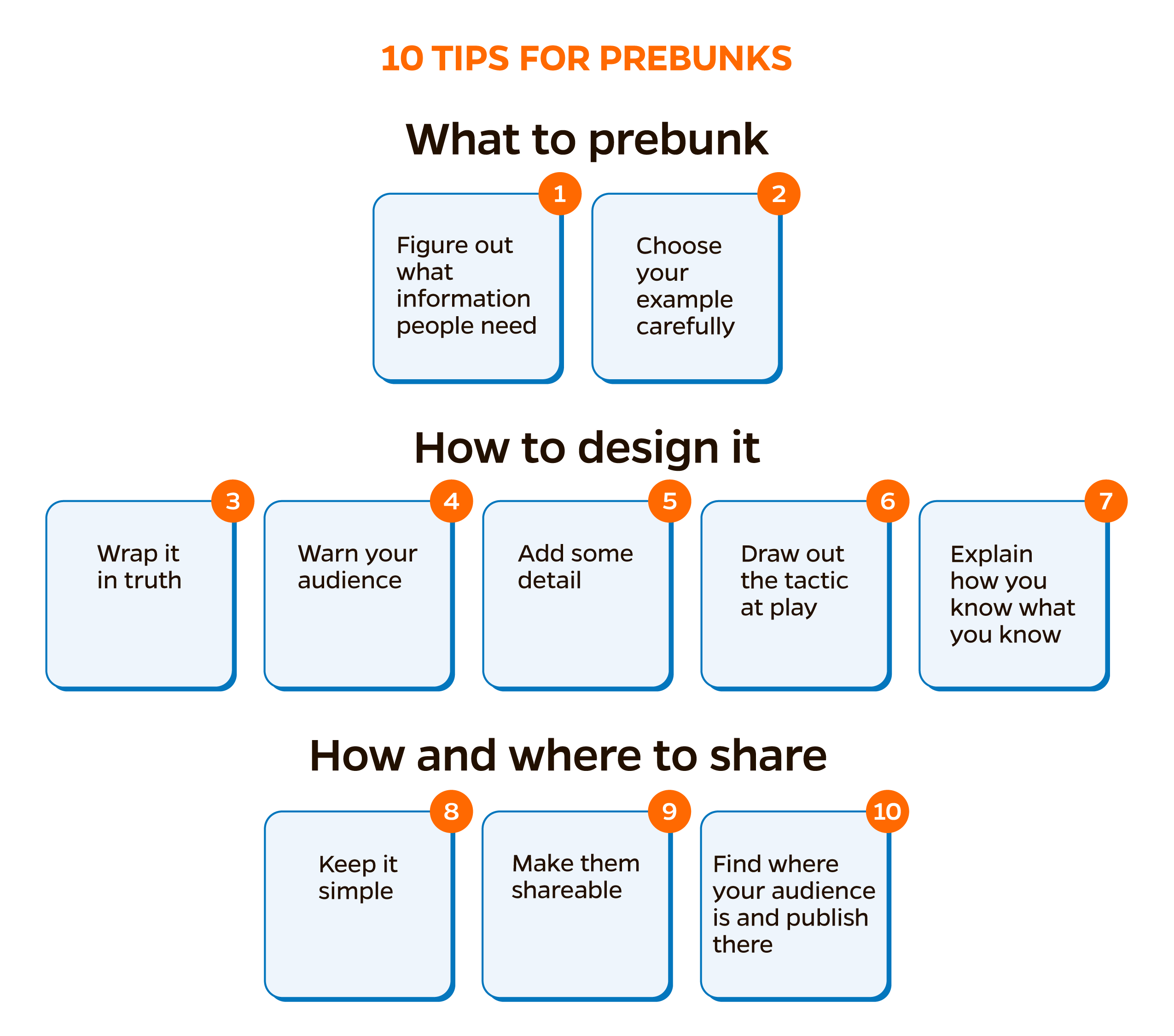

Task 3.3: Develop prebunking and inoculation messages

Prebunking is a process to “inoculate” people against misleading claims, like vaccination against a disease.12 The idea involves showing people examples of misleading content and explaining the tactics typically used to persuade beliefs. By providing that information, individuals are better able to understand and identify rumors and flase narratives when they arise, less likely to spread or share those claims, and less likely to be persuaded by or believe misleading claims when exposed to them.13-17

The first steps to developing prebunking messages include the previous 2 tasks, understanding possible rumors and how they resonate with local community needs and values. Existing guidance on prebunking approaches focuses on telling the truth; exposing known tactics, such as attributing misleading content to “experts”; and warning of expected rumors.18-21 The figure below, based on research from First Draft, provides more information on developing prebunking messages.21 Public health departments can also use gamified prebunking tools, such as Bad News and Go Viral!.22,23 For more information about prebunking and when or how to use it, see our Practical Playbook for Addressing Health Rumors.8

Figure 1. Tips for developing prebunking messages, adapted from First Draft News19

Activity 4: Promote use of and access to trusted sources

People are less likely to trust or turn to misleading claims if they have the skills or knowledge to identify rumors as untrustworthy or false and if they have easy access to information from official sources, like the public health department.

Task 4.1: Facilitate access to trustworthy health information and teach critical thinking skills to enhance information self-sufficiency

Improving public resilience to misleading health information is the ultimate goal of public health communicators. Cultivating a resilient public involves providing access to and tips on how to find trustworthy sources for health information and teaching critical thinking skills to help people collect and evaluate health information.8,24,25 Working with public health colleagues involved with other behavior change efforts, such as chronic disease prevention or tobacco control, as well as trusted community partners, is beneficial. For instance, including health and digital literacy training on various public health topics in school curricula or during presentations at other community venues can be helpful.26

Task 4.2: Enhance information accessibility and understandability

Effective public health communication requires accessible and understandable content.27,28 Translators and accessibility experts are important to creating communication materials in languages and formats that intended audiences can understand. Materials should not only be readable but also culturally relevant. Leveraging the knowledge of community members, including public health colleagues, or CBOs can help improve information dissemination. Translation services should be set up before health emergencies, as contracting and funding mechanisms can slow timely delivery when information is changing quickly. Additionally, public health staff can provide clear guidance on where to go for additional culturally or linguistically appropriate health information, such as CBOs or trusted online resources.2

Priority 4 References

References

- Schoch-Spana M, Gronvall G, Brunson E, Sell TK, Ravi S, Shearer MP, Collins H. How to Steward Medical Countermeasures and Public Trust in an Emergency: A Communication Casebook for FDA and its Public Health Partners. Baltimore, MD; UPMC Center for Health Security; 2016. https://centerforhealthsecurity.org/sites/default/files/2022-12/fdacasebook.pdf

- Potter CM, Grégoire V, Nagar A, et al. A practitioner-focused checklist to build trust, address misinformation and improve risk communication for public health emergencies. [Manuscript submitted for publication.]

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Resources for Emergency Health Professionals: Crisis & Emergency Risk Communication Manual and Tools. Updated January 23, 2018. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://emergency.cdc.gov/cerc/resources/index.asp

- Admin B. Making Public Health Visible. Big Cities Health Coalition. Published April 2, 2018. Accessed June 7, 2024. https://www.bigcitieshealth.org/front-lines-blog-making-public-health-visible/

- O'Malley P, Rainford J, Thompson A. Transparency during public health emergencies: from rhetoric to reality. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87(8):614-618. doi:10.2471/blt.08.056689

- Hodson J, Reid D, Veletsianos G, Houlden S, Thompson C. Heuristic responses to pandemic uncertainty: Practicable communication strategies of “reasoned transparency” to aid public reception of changing science. Public Underst Sci. 2023;32(4):428-441. doi:10.1177/09636625221135425

- Nagar A, Huhn N, Sell TK. Summary Report for Task 8: Identify and analyze health-related rumors related to past public health emergencies. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security; 2023.

- Nagar A, Grégoire V, Sundelson A, O’Donnell-Pazderka E, Jamison AM, Sell TK. Practical Playbook for Addressing Health Rumors. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security; 2024.

- Google News Initiative. Google Alerts: Stay in the know. Undated. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://newsinitiative.withgoogle.com/resources/trainings/fundamentals/google-alerts-stay-in-the-know/

- Talkwalker. Free Social Media Monitoring Tools. Undated. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://www.talkwalker.com/free-social-media-monitoring-analytics-tools

- Ecker UKH, Lewandowsky S, Cook J, et al. The psychological drivers of misinformation belief and its resistance to correction. Nat Rev Psychol. 2022;1(1):13-29. doi:10.1038/s44159-021-00006-y

- Harjani T, Roozenbeek J, Biddlestone M, et al. A Practical Guide to Prebunking Misinformation. Cambridge, England: University of Cambridge, Jigsaw (Google), BBC Media Action; 2022. https://prebunking.withgoogle.com/docs/A_Practical_Guide_to_Prebunking_Misinformation.pdf

- McGuire WJ. Inducing resistance to persuasion. Some contemporary approaches. In: Haaland CC, Kaelber WO, eds. Self and Society. An Anthology of Readings. (1981 ed.) Lexington, Massachusetts: Ginn Custom Publishing; 1964:192-230.

- Basol M, Roozenbeek J, Berriche M, Uenal F, McClanahan WP, Linden SV. Towards psychological herd immunity: Cross-cultural evidence for two prebunking interventions against COVID-19 misinformation. Big Data Soc. May 11, 2021. doi:20539517211013868

- Saleh NF, Roozenbeek JO, Makki FA, McClanahan WP, van Der Linden S. Active inoculation boosts attitudinal resistance against extremist persuasion techniques: A novel approach towards the prevention of violent extremism. Behav Public Policy. February 1, 2021. doi:10.1017/bpp.2020.60

- Iles IA, Gillman AS, Platter HN, Ferrer RA, Klein WM. Investigating the potential of inoculation messages and self-affirmation in reducing the effects of health misinformation. Sci Commun. October 5, 2021. doi:10.1177/10755470211048480

- van der Linden S, Leiserowitz A, Rosenthal S, Maibach E. Inoculating the public against misinformation about climate change. Glob Chall. January 23, 2017. doi:10.1002/gch2.201600008

- Roozenbeek J, van der Linden S, Nygren T. Prebunking interventions based on ‘‘inoculation’’ theory can reduce susceptibility to misinformation across cultures. Harv Kennedy Sch Misinformation Rev. February 3, 2020. https://misinforeview.hks.harvard.edu/article/global-vaccination-badnews

- Garcia L, Shane T. A guide to prebunking: a promising way to inoculate against misinformation. First Draft. Published June 29, 2021. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://firstdraftnews.org/articles/a-guide-to-prebunking-a-promising-way-to-inoculate-against-misinformation

- Cook J, Lewandowsky S, Ecker UK. Neutralizing misinformation through inoculation: Exposing misleading argumentation techniques reduces their influence. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0175799.

- UNICEF Middle East and North Africa, Public Goods Project, First Draft, Yale Institute for Global Health. Vaccine Misinformation Management Field Guide. UNICEF; 2020. https://www.unicef.org/mena/reports/vaccine-misinformation-management-field-guide

- Social Decision-Making Lab at the University of Cambridge, Tilt, Gusmanson. Bad News. Undated. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://www.getbadnews.com/books/english

- Social Decision-Making Lab at the University of Cambridge, Drog, Tilt, Gusmanson, UK Cabinet Office. Go Viral!. Undated. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://www.cam.ac.uk/stories/goviral

- Howell EL, Brossard D. (Mis)informed about what? What it means to be a science-literate citizen in a digital world. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021;118(15):e1912436117. doi:10.1073/pnas.1912436117

- Wang S. Back to the Basics: Education as the Solution to Health Misinformation. Harvard Political Review. Published February 6, 2023. Accessed June 7, 2024. https://harvardpolitics.com/basics-health-misinformation/

- Sundelson AE, Jamison AM, Huhn N, Pasquino SL, Sell TK. Fighting the infodemic: the 4 i Framework for Advancing Communication and Trust. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):1662. doi:10.1186/s12889-023-16612-9

- Flores AL, Meunier J, Peacock G. "Include Me": Implementing Inclusive and Accessible Communication in Public Health. Assist Technol Outcomes Benefits. 2022;16(2):104-110.

- Public Health Communications Collaborative. Plain Language for Public Health. Public Health Communications Collaborative; 2023. https://publichealthcollaborative.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/PHCC_Plain-Language-for-Public-Health.pdf