COVID-19 and Vaccine Mandates

Two experts discuss what makes mandates necessary, effective, and ethical.

The summer arrival of the COVID-19’s highly infectious Delta variant triggered a wave of hospitalizations and deaths, primarily among the unvaccinated.

In response, President Biden on September 9 ordered broad mandates aimed at tamping down the spread of the virus. The measures require businesses with more than 100 employees to be vaccinated or tested weekly. The mandates also apply to health care workers and federal contractors.

Predictably, the move has generated strong opposition from groups who argue that the government does not have the power to compel vaccination and equally strong responses from public health officials who say that the time has come for mandates to be put in place.

In a Q&A, Nancy Kass, ScD ’89, a professor in Health Policy and Management and Phoebe R. Berman Professor of Bioethics and Public Health; and Saad Omer, MBBS, PhD ’07, MPH ’03, director of the Yale Institute for Global Health, discuss when public health mandates should be considered and what makes an effective—and ethical—mandate.

When in a public health crisis is it time to consider mandates?

Nancy Kass: Public health rarely starts with a mandate as Plan A. In general, public health will do exactly what happened with COVID vaccines, which is try to help the public understand why a vaccine is effective, how a vaccine is safe, and execute its responsibility for making it accessible in all senses of the word—cost, location, language. If it turns out that doing all of those things leads to sufficient coverage, mandates aren't needed. You’re able to maximize this ethical goal of respecting people's autonomy and freedoms—and maximize the benefits that we need from a public health perspective.

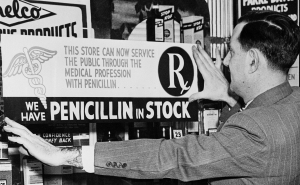

If it turns out that that doesn’t happen, that’s when mandates come into play. It’s the same thing that happened with wearing seatbelts, with smoking in restaurants: Plan A was education. It was only when that didn’t influence sufficient [numbers of] people, and it was important enough from a public health perspective, that mandates become an important tool.

Mandates in general depend on there being a really large and consequential public health threat and that less intrusive measures have not been sufficiently effective. All of these things are essentially justifying why it’s OK to overrule the wishes of some people who didn’t want to get vaccinated.

Can you talk about the criteria you proposed last year for a vaccine mandate?

Saad Omer: In June 2020, colleagues and I published a paper with six criteria for a COVID-19 mandate based on science and ethics, including that mandates should be implemented only if the COVID-19 containment is not adequate and that evidence of the safety and efficacy of the vaccine has been transparently communicated. We now have met those triggers for sub-populations, like certain employers and universities, but not for the general population.

When is it not appropriate to turn to mandates?

SO: Implementing too early could drown out the voluntary response. And there are ethical reasons as well; you do the least intrusive intervention at a given time to get the same effect. And if you don’t have [vaccine] access covered, you could also exacerbate inequities.

What makes an effective mandate?

SO: I take a middle-of-the-road approach to vaccine mandates. Some people think that the only way to implement a mandate is a draconian approach of picking up people from their homes and jabbing them with a shot. That’s not how modern mandates work. They are tied to a benefit, a privilege, or a service, and getting vaccinated becomes a condition of availing yourself of that opportunity.

If you have a mandate that’s too easy to opt out of, you don’t get that much response. In the case of a mandate for childhood vaccines, [for example,] if you can go to your health department’s website, print an exemption form, and just check a box, you don’t get that high-end effect of your mandate.

In a different scenario, in 2011 Washington state added a requirement where if you are opting out of the vaccine for non-medical reasons you have to go to a health care provider, you have to have counseling, and you have to sign what’s called an informed declination form. When they did that, they had a more than 40% drop in their exemption rates.

So the bottom line is, don’t make it too easy but don’t make it impossible to opt out. A Goldilocks approach is the optimal approach.

From an ethical perspective, how would you respond to someone who is adamantly opposed to getting vaccinated?

NK: People who are opposed to mandatory vaccination will often say, “I ought to have the freedom to decide what to do with my body.” Very often in public health there is a view that agrees with that, that says, Let’s inform people and allow them to make the choices that they feel are right for them.

Where vaccination for something like COVID becomes different is that when someone chooses not to be vaccinated out of, for example, freedom to make that choice, it impacts the freedoms for everyone else. We’re seeing right now that a lot of places that had opened up and eliminated mask mandates are now going back to mask mandates. So the choices that people make to not be vaccinated—while genuinely they may really feel like it’s a personal choice—end up impacting the freedoms of others.

SO: I grew up in a country where when I was young there was a dictatorship, so I don’t take questions of personal liberty lightly. But here’s the problem with infectious diseases: They are just that—infectious. So your choice of staying unvaccinated impacts me and my loved ones.

Therefore, even if you have the most libertarian perspective on life, vaccines and infectious diseases can be, and should be, and must be an exception. Because you’re taking away the liberty for me to exist. And in the life, liberty, and happiness cadence, I think a smartly designed mandate threads the needle very appropriately.

Looking ahead, do you think resistance to vaccine mandates will wane?

NK: My hypothesis is that the more it becomes normal for big national employers and little local employers to say, “To work here, to keep our customers and clients safe, we’ve decided we’re going to do this,” the more I believe it really will be normalized. It’s not simply that people will have fewer options to get out of it. I genuinely believe that fewer people will insist that they need to have an option to get out of it.

In watching what’s going on in different states right now with the Delta variant, it seems like some of that is [already] happening. But there’s also something else going on: Governors or other elected representatives in states where there has been more opposition to vaccines and vaccine mandates are faced with hospitals that have no more bed capacity, and [they] are starting to advocate for vaccination in order to help save the state.

RELATED CONTENT

How COVID-19 Vaccine Mandates Have Played Out (podcast)

The Politicization of COVID-19 Vaccines (podcast)