Why Eli Lilly’s Insulin Price Cap Announcement Matters

This article was updated on March 15, 2023, to reflect Novo Nordisk's latest announcement.

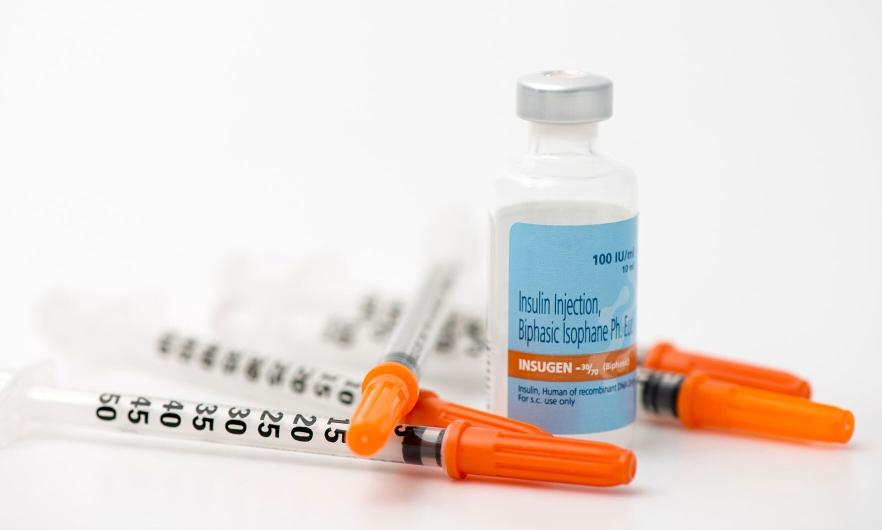

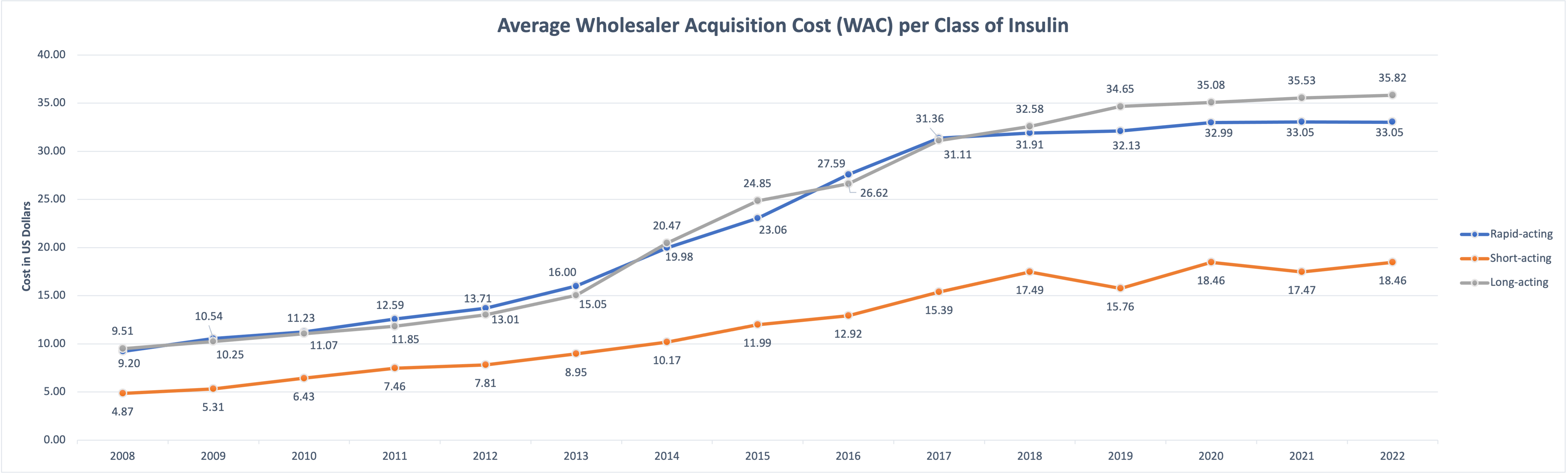

Insulin affordability has consistently been in the news over the last few years in the U.S.—and for good reason: The drug’s price has risen more than 300% in the last 20 years, forcing many Americans, even those with insurance, to ration or hoard the lifesaving drug that millions rely on daily.

“A lot of individuals of all different demographics reported having to cut their doses of insulin or even forgo insulin altogether because of the price,” says Mariana Socal, MD, PhD ’17, MSc, MPP, an associate scientist in Health Policy and Management.

During the State of the Union address in January, President Biden announced that as part of the Inflation Reduction Act, insulin will be capped at $35 per month for seniors on Medicare. He also expressed his commitment to making this lifesaving price cap available to all Americans.

Eli Lilly, one of the largest insulin manufacturers in the U.S., heard that call and announced on March 1 that they would lower their list price of insulin by 70% and cap insulin co-pays at $35 for those with commercial health insurance and uninsured patients (a policy that already existed through their Insulin Value Program).

Several manufacturers were already offering the $35 cap during the pandemic for economic relief, but it wasn’t widely known, says Socal.

Who benefits from this price cap?

People with government insurance, such as Medicaid recipients, are excluded from the $35 monthly cap, according to a company press release.

And Lilly’s cap may not change much for those with commercial insurance plans that have set co-pays. In these plans, insurers likely already had a $35 limit in place because they pay much less than that 70% discounted price.

This price cap will help those with high-deductible insurance or plans that come with a high cost-share instead of set co-pays. In these cases, the insurer might pay 80% of the cost and the patient would cover the remaining 20%—of the drug’s list price—a massive financial burden for many.

The burden is even greater on the uninsured, who, without a price cap, could pay as much as $275 per vial ($27 per 1 mL) and may need several vials per month. A 2022 study found that 14% of Americans who use insulin spent a “catastrophic” 40% or more of their available income on the drug.

Source: Data from SSR Health.

Given these astronomical costs, Socal called Lilly’s move “an important shift in a manufacturer's behavior”—noting that it’s the first time an insulin manufacturer has lowered the drug’s list price and publicly announced it.

But this is not pure altruism, Socal notes. “Even though they're dropping their list price by 70% and capping their cost to patients at $35, it’s important for us to make this very, very clear—the company is still making a profit,” she says.

How did insulin get so expensive?

For decades, insulin manufacturers have claimed that their high prices are necessary to spur innovation and investment in research and development. But there’s another key factor in the high cost of insulin: pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), third-party companies that manage prescription drug benefits for health insurers, explains Socal.

During a 2019 congressional hearing, insulin makers admitted that there’s pressure to keep list prices high so that PBMs can also profit.

PBMs favor the drugs that will yield them higher profits. By lowering prices, Lilly runs the risk of being excluded from formularies, meaning the insurance companies will no longer cover the product for their patients.

But the move was nonetheless a strategic one. As new generics are set to become available and add competition to the market, Lilly is “just jumping ahead of the curve and trying to maintain their market share by behaving how they think other products will behave,” says Socal.

It’s possible that Lilly may have set a new standard. On Tuesday, March 14, 2023, Novo Nordisk joined Lilly and announced that they would cut the list price of its NovoLog insulin by 75% and the prices for Novolin and Levemir by 65% starting in January 2024. It remains to be seen whether Sanofi will follow in Lilly's and Nordisk's footsteps. If all three dominant insulin manufacturers do this, will PBMs have to agree to accept lower profits? Socal says we will have to wait and see.

Grace Fernandez is a communications associate in the Office of External Affairs at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.