Advancing Human Rights in Afghanistan

75 years after it was signed, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is the world’s most translated document—but implementing it presents constant challenges.

December 10 marks the 75th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The United Nations document set out for the first time a protocol of fundamental human rights to be universally protected, with the core ambition to “infuse societies with equality, fundamental freedoms and justice.”

It is the most translated document in the world—but implementing it presents constant challenges for countries and the international community.

Nadia Akseer, PhD, MSc, a native of Afghanistan and an assistant scientist in International Health, is a winner of the inaugural Sommer Klag Advocacy Impact Awards. The $40,000 award is intended to support Akseer’s advocacy work through her project, Mission Afghanistan 2030 (MA2030). The initiative is a working group at the Bloomberg School that advocates for the basic rights of people in Afghanistan, who have faced decades of grinding poverty, ongoing conflict, and an exodus of donor support since the Taliban takeover in August 2021. The project aims to bring together a diverse network of stakeholders including researchers, NGOs, donors, and the Afghan diaspora to collaborate on research, evaluation, advocacy, and impact opportunities that can support health in Afghanistan.

Akseer talks about the challenges of achieving the Declaration’s aims in Afghanistan and why the document remains essential to advancing human rights.

Tell me a little about you and how Mission Afghanistan 2030 began.

In September 2021, shortly after the Taliban takeover, I started Mission Afghanistan 2030, which is focused on bringing together people to do research, advocacy, education, and evaluations to advance programming for Afghanistan. The goal of MA2030 is to protect the health and other basic rights of Afghans by supporting their humanitarian and development needs for achieving their sustainable development goals by 2030. I'm hoping that we can, within that lens, have some good productive dialogue. So far, we’ve been focused on media outreach as well as pursuing several research studies, and planning a visit to Afghanistan to assess the needs on the ground that we can help support. We’d like and use that wisdom to foster conversations between donors, the international community, and NGOs.

When it comes to advocating for basic rights in Afghanistan, which areas are most challenging to protect?

Afghanistan is struggling in all areas when it comes to human rights. Having a roof over your head, access to clean water, access to good food—these basic rights that anybody needs to have a good standard of living are virtually impossible or very difficult to get in Afghanistan today.

Gender equality and education for women, which go hand in hand, are particularly challenging. Currently, Afghanistan is the only country in the world that has banned the education of women beyond the sixth grade.

The regime does not want to entertain this topic at all, not with their Muslim country peers, not from people within the country, not from the diaspora, not from the international community.

The Mission is really trying to advance these rights as much as possible—but this needs to be done carefully. It needs to be done in the context of Islamic culture, principles, and societal norms—and then supported with the data and evidence that show how letting girls go to school benefits the country's development.

Some donors are withholding funds to both humanitarian and development programs if the Taliban is not ensuring girls go to school. That’s also not the right approach, because it means that funding is being withheld from the people.

In the context of the Declaration, where has Afghanistan seen the most progress?

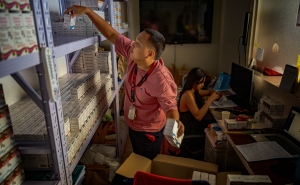

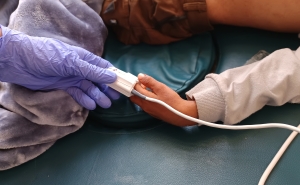

The right to health is something that the current regime has not pushed back on. They want people to be healthy; they don't want them to be dying in the streets, so it’s much easier to intervene on health than it is for education and some other areas.

Seventy percent of children in Afghanistan are still malnourished. Our mission is to take the current global guidelines and evidence and contextualize them for Afghanistan and make recommendations to the regime and to donors that promote the right to health—that children should get [adequate] nutrition through the first two years of life.

Given the major challenges in upholding the Declaration in Afghanistan and elsewhere, does it still hold value to you and your work?

These types of agreements are still necessary. As civilizations, and as humanity, we need basic standards to live by. If countries can uphold them and communities can also participate in them, that’s a wonderful thing. The reality is often very different. And it's not just the case in Afghanistan. It's in a lot of countries struggling with implementing the Declaration to varying degrees in programs and policies.

The international community, including the United Nations, has to ensure that they don't have double standards when it comes to the Declaration, in terms of the global financial flows and global policy.

How has that inconsistency played out in Afghanistan?

Commitments dwindle when the international community loses interest. The U.S. was in Afghanistan from 2001 to 2021, and in that time did a lot to advance the rights of Afghans, building clean water systems, schools, and health care facilities.

But once the regime changed, they sort of abandoned the country and took the money away. That's where the double standard comes in.

The inconsistent commitments of international leaders are a stubborn problem. You’ve advocated for social protections to help communities be more immune to these changes—what do you mean by that?

My idea for social protection is to have a remittance-based system—a buffer or fund for Afghans where the diaspora can pool funds and provide a baseline to support the poorest people in Afghanistan. There is a precedent for it in the world. For example, remittances from the diaspora have been critical for social resilience and health outcomes in Nepal and the Kyrgyz Republic.

It provides a level of protection when a regime changes or some kind of catastrophe hits the country.

These social protections can come in the form of cash transfers, health insurance or social benefits from the government—but they can be most effective when they come from the diaspora that's working outside of the country because those funds are not impacted by a regime change or a donor decision to suspend a program.

There are millions of Afghans all over the world like me who are established in other countries. We have jobs, and we have careers, and are trying to rebuild our country from afar.

Annalies Winny is a writer and producer at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.