The Polio Outbreak and What Needs to Be Done To Eradicate the Virus Globally

Just a generation or so ago, tens of thousands of people in the U.S.—mainly children—were afflicted by paralytic poliovirus.

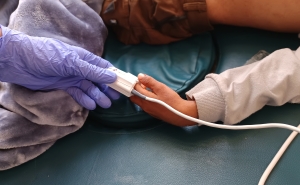

In 1955, an inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), which contained a “killed” version of the virus and was delivered as a shot, was introduced. In 1961, an oral polio vaccine (OPV) containing a weakened or “attenuated” live version of the virus made widespread vaccination much easier around the globe because it could be administered by oral drops and not through needles.

Thanks to massive vaccination campaigns around the world, polio cases dropped by 99% since the late 1980s and, until recently, remained endemic in only two countries. But now, evidence of polio outbreaks is showing up in wastewater in U.S. cities. Just this summer, the U.S. saw its first case of paralytic polio in decades.

Olakunle Alonge, MD, PhD ’13, MPH ’09, an associate professor in International Health, studies global polio eradication efforts. In this Q&A, adapted from the [date] episode of Public Health On Call, Alonge talks with Joshua Sharfstein about the current polio outbreaks and what we can do about them.

Public Health On Call

This article was adapted from the August 24 episode of Public Health On Call Podcast.

Polio is caused by a virus. What can you tell me about the virus?

The virus is transmitted by ingesting contaminated food or drinking contaminated water, through what we call the oral-fecal route.

In its severest form, polio causes damage to the nerves that control some of our voluntary muscles, including the muscles we use to walk, hold things, breathe, talk, and so on.

In most cases, it causes a mild form of illness that presents almost like the regular flu or some other kind of minor viral infection—basically fever, muscle ache, and headache. But about 25% of people that get infected could have meningitis, with neck stiffness and a lot of pain. In very rare cases—maybe 1 in 100 to 1 in 500 cases—there is what you call acute flaccid paralysis, which usually involves weakness and paralysis of the muscles of the lower limbs.

That’s how we think about this in the United States—the pictures of kids in the iron lungs from paralytic polio. What’s the history of polio around the world?

In 1988, the world got together to eradicate polio. At that point, there were fewer than 50,000 cases reported annually. Since that time, there have been concerted efforts through vaccination programs and community engagement to address polio.

Right now, the wild poliovirus is endemic in two countries: Pakistan and Afghanistan. We also have seen about a 99%reduction in cases, to fewer than 15,000, than what was recorded at the onset of the eradication program.

But the eradication effort has also created some challenges, particularly for the viruses derived from the polio vaccine itself. We do see cases of vaccine-derived poliovirus—which is different from the wild poliovirus and which is what we see emerging in more countries.

How does that happen? How does a vaccine virus turn into an infection?

To answer that question, we have to talk about the two types of vaccines that we have for polio.

One of the commonly used vaccines is what we call the oral polio vaccine (OPV). This vaccine contains the virus itself. Even though it’s attenuated or weakened, it’s still the live virus.

The second type is the inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), which contains a killed version of the virus.

In a number of countries outside the U.S., OPV is the mainstay of vaccination programs for a lot of reasons: It’s easy to administer for community campaigns, [for example]. But in some very rare instances—1 in maybe 2.5 million cases—when you administer the polio vaccine, you could have a scenario where the OPV virus is transmitted from somebody who received the vaccine to somebody who is susceptible, meaning they have no immunity to polio.

When the virus is transmitted to a susceptible host, it can replicate. While it replicates, genetic changes can happen that allow the active virus in the vaccine to revert back to a strain that can cause damage. That’s what is happening now, and there are a number of factors that can lead to that.

Are there certain factors that make that more likely?

Yes. The important thing to recognize is that if [most] people have immunity, the number of people susceptible to being infected by the vaccine strain of the virus is going to be almost nonexistent. The critical element is ensuring that there’s adequate vaccination coverage within a population.

Some of the outbreaks of vaccine-derived poliovirus happen in populations without enough immunization coverage.

How many countries around the world in a given year will see a case of the vaccine-derived polio infection?

As of 2020, there were about 33 countries that reported an outbreak of vaccine-derived poliovirus. Where we have seen paralytic polio—which, in this country, is linked to community transmission of the vaccine-derived virus—that’s about 1,500 cases [a year, globally].

That’s the fear right now in the U.S. and other countries that haven’t seen polio: the potential that the vaccine-derived virus could find pockets of unvaccinated people.

That’s partly right. The majority of the concern is related to vaccine-derived polioviruses.

But the same factors that allow for the vaccine-derived viruses to cause paralysis and infection also apply to the wild poliovirus. When you have a community with low immunity, and you have someone come from one of the endemic countries to the U.S., you could have an outbreak.

So, we’re really talking about susceptibility to polio of any kind when vaccination rates go down.

That’s correct.

Given the number of cases related to the OPV, have people considered switching to the inactivated version?

There are really no straightforward answers.

Both the OPV and the IPV that are given as a shot play a critical role in the eradication program. In countries like the U.S. that have the resources and the means, obviously, it’s advantageous to only use the IPV. That’s been the recommendation since 2000.

But in countries where we have OPV still in use, there are a lot of reasons why this is the case. One, obviously, is [not having] the resources and capacity to be able to provide the IPV.

The OPV also has other advantages for rapidly addressing person-to-person transmission in communities because it actually prevents not just the disease, but the infection as well.

So the fear would be that if you switch just to the inactivated, or killed, vaccine, you wouldn’t be able to vaccinate as many people in some of these countries and they could be susceptible to major outbreaks of poliovirus.

That’s correct.

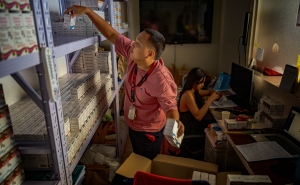

There are two factors. One: The world doesn’t, as of now, have enough supply of IPV to cover all of the population. Two: You need a relatively stable health system in order to administer shots. You need doctors, nurses, and clinicians as opposed to just going from house to house giving drops of the OPV. So, it’s the issue of capacity.

If we asked the rest of the world to switch to the IPV, it’s likely going to create more problems than solve the ongoing issues we have with the live vaccine.

One of the reasons we have a significant outbreak of vaccine-derived polio viruses has been linked to the way the global community managed the switch from one type of vaccine to another. We have different types of OPVs: We have OPV1, OPV2, OPV3 … OPV2, which addresses the wild poliovirus type 2, was a candidate for the switch in 2016.

In 2016, although the wild poliovirus type 2 had been completely eradicated globally, the [vaccine-derived] poliovirus from OPV2 was still in circulation and susceptible populations (those without any immunity to poliovirus type 2) were at risk of being infected. So, there was a switch to encourage all countries to use IPV2—that is, to replace OPV2 with IPV2—in all communities.

But there weren’t enough IPV doses [or the] capacity to administer. So there was an immunity gap for the type 2 virus, which led to the circulation of vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2, which is the most common type of virus and continues to transmit.

We’re now finding evidence of poliovirus in the sewage in New York, for example, and other places may follow suit. What is your advice for the U.S., which has not seen a case of paralytic polio for many years and now suddenly has one?

One of the major things is vaccination. You want to really target those pockets of the population where the vaccine coverage for polio is low.

You can’t address low vaccination without overcoming some of the root causes of low vaccine coverage, and those causes vary from community to community. So you really have to engage with the community. Yes, you have an evidence-based vaccine, but that doesn’t necessarily translate to impact as we’ve seen not just in the U.S., but in a number of countries. You really have to be talking to the community to find the solutions to get at some of the societal and social problems of vaccine refusal.

The second thing is you have to be able to respond to outbreaks quickly. One of the main strategies is environmental surveillance, where we test wastewater to see the strains of viruses within the community. You tend to see vaccine-derived viruses in wastewater weeks before you see cases of paralytic polio in the community. Responding adequately to surveillance findings is crucial. When you see environmental cases, you need to do campaigns in affected communities.

You have worked on polio for many years all over the world, and now you’re seeing the U.S. touched by this. What are your thoughts about global eradication in this context?

There are silver linings to this. One is the fact that this is most likely to help the global polio eradication initiative. We don’t want cases in the U.S., the U.K., or in Europe, but these outbreaks allow people in these countries to see that polio is still very much with us. We’ve seen that a lot of this transmission came from outside of the U.S. and the U.K., so we begin to recognize the interconnectedness of communities.

For a successful eradication program, all hands must be on deck. I think the fact that we are seeing cases in the U.S. draws the attention of legislators and people who have the means and influence to rally around the eradication initiative.

Some of the challenges the initiative has had are related to political will and advocacy. The influence of countries like the U.S. and U.K. and other western nations can really translate positively for the global eradication initiative.

If eradication succeeds and there is no more polio on the face of the earth, then no one needs to be vaccinated, right?

Absolutely. We win together or fall together.

Olakunle Alonge, MD, PhD ’13, MPH ’09, is an associate professor in International Health.

Joshua Sharfstein, MD, is the vice dean for Public Health Practice and Community Engagement and a professor in Health Policy and Management at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. He is also the director of the Bloomberg American Health Initiative and a host of the Public Health On Call podcast.