A Global Snapshot of Family Planning and Reproductive Freedom

Working toward a world where everyone can attain their reproductive goals

The International Conference on Family Planning (ICFP), the largest gathering of its kind, begins today in Pattaya, Thailand. Advocates, researchers, scientists, government leaders, health practitioners, and others from 125 countries will convene to discuss universal access to family planning.

In this Q&A, adapted from the November 14 episode of Public Health on Call, Stephanie Desmon talks with Megan Christofield, MPH ’11, senior technical adviser and project director of Jhpiego’s Family Planning team, about the future of family planning, including shifting political barriers, funding shortfalls, game-changing self-injectable contraceptives, and the path to helping all individuals achieve their reproductive goals.

Public Health On Call

This article was adapted from the November 14 episode of Public Health On Call Podcast.

What is the state of global family planning right now?

Family planning is what I live and breathe. These are really exciting times in family planning and [there has been] a lot of progress in the field. But it's also precarious, with political shifts in the U.S. and around the world that are creating a bit of a fragile environment for family planning.

When we're talking about family planning, we’re talking about the ability of individuals and couples to anticipate and attain their desired number of children, and the spacing and timing of those pregnancies and births. And when we're thinking about family planning and what we're aiming for, what our goals are—it's really a world where every person can attain their reproductive goals. Whether that is to have children, to prevent or space their childbearing, or even if an individual is waiting in some ambivalence around childbearing—we're here to hope and deliver on this idea that the information and systems are equipped and ready to support people in realizing those goals, meeting them where they are over the course of their reproductive lifetimes.

How well are we doing?

We don't quite have the metrics that tell us whether every person is achieving their reproductive goals, but in the meantime, we track proxy indicators that give us a picture of performance.

First and foremost, we look at the prevalence of modern contraceptive use—the rate at which women of reproductive age are using modern contraceptives. We can look at that rate over time. Family Planning 2030, which is sort of the global umbrella partnership that guides the entire community, reports that between 2010 and 2020, modern contraceptive use has increased across Africa and the Latin America and Caribbean region, but it has remained unchanged in Asia and the Pacific. For example, in Africa as a whole—and of course, that is a broad and diverse continent—contraceptive prevalence increased from about 21% in 2010 to 27% in 2020. In the Latin American region, it increased from 52% to 55% over that same decade, while in Asia and the Pacific, it remained stagnant around 46%.

To give you a sense of how that translates, that use equates to 357 million women and girls who are using modern contraception in low- and middle-income countries.That means over just the past year, those 357 million contraceptive users have averted 135 million unintended pregnancies, 28 million unsafe abortions, and 140,000 maternal deaths. This is a huge impact that contraceptive use is having, which is really exciting.

How is the demand being met?

We want to look at contraceptive use not just as absolute numbers and rates of use, but to what extent we are meeting the demand of individuals who want to prevent their next pregnancy or stop childbearing altogether? The slightly more nuanced take is: To what extent is demand for family planning being met? We call this demand satisfied. This narrows our denominator to those who actually want to prevent or stop childbearing altogether.

In low- and middle-income countries, this demand-satisfied indicator currently sits at about 51% in sub-Saharan Africa and 76% in Middle Eastern and North Africa, with other regions sitting in between those numbers. We are seeing some impressive rates of demand satisfied, but a bit of a way to go as well.

If you flip that indicator of demand satisfied to who we're missing, that’s what we call unmet need. Unmet need is those who do have an interest in spacing or limiting their next pregnancy, but are not currently using any method of modern family planning to do so. We know that there are over 200 million women and girls in low- and middle-income countries who meet that criteria, so there’s a big opportunity there.

Why is there so much unmet need?

There are a lot of reasons: Do people have the products that they can tolerate, that they can live with, that would help them plan their pregnancy? Do they have services available to them, delivered in a way that meets them where they are? We also have social and cultural norms that continue to inhibit women’s and girls’ access to basic health care, unfortunately.

Where are we with funding? Where do we need to be?

This is really top of mind for many of us in the family planning space because, frankly, funding levels are really insufficient for delivering on our ability to help individuals reach their reproductive goals. U.S. government funding for international family planning and reproductive health has been stagnant for over 10 years now. It's hovering around $600 million per year, which accounts for about 5% of the U.S. global health budget. And overall, bilateral disbursements for family planning per year reach about $1.5 billion, largely because of that U.S. contribution, but also from donors like the United Kingdom, Sweden, the Netherlands, France, Germany, etc.

I don't think reliance on donor funding is the only answer. There are some impressive gains in getting country governments and other local resources to commit budgets to family planning, which is very exciting. That trend will hopefully continue.

But in the meantime, the stagnancy [in funding] could shift the burden for paying for family planning to family planning users themselves, who may not have the resources to access or continue to use family planning. This is concerning. We want to make sure that folks have all of their preventative care covered so they can live healthy and thriving lives.

What are we seeing in the expansion of contraceptive methods?

I am so excited about this. Here's why. We know that for every new contraceptive method that is added to a country's available methods, their overall contraceptive prevalence will rise 4% to 8%, which is really phenomenal when you think about some of the statistics I shared earlier.

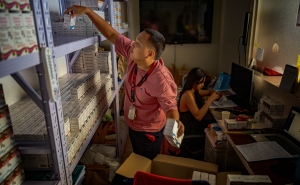

Right now, there are major efforts underway to expand access to new and underutilized methods, like the hormonal IUD. This is the fastest-growing method of contraception in the U.S., and it’s finally gaining some traction in low- and middle-income countries because lower-cost versions have entered the market. I'm really excited to see how this method is received as its introduction scales in Madagascar, Kenya, Zambia, and elsewhere.

The other product that has a lot of people's attention right now, and certainly will be discussed a lot at the ICFP, is the self-injected contraceptive DMPA-SC—brand name Sayana Press—which is just a game changer. Traditionally, we've had intramuscular injectable contraceptives, a traditional kind of vial and syringe that have been widely available and utilized around the world, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. In the U.S., you might know these products by names like Depo-Provera.

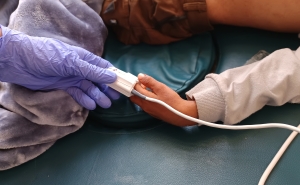

Sayana Press is a slightly lower dose of the same hormone, packaged into a prefilled, single-use plastic device with a short needle for injecting the contraceptive into the fat underneath the skin rather than intramuscularly. It's injected quarterly, it's 99% effective, and because of the way it's formulated and packaged, it can be administered by any trained person—whether a community health worker, a pharmacist, or the woman herself. So an individual can, say, take home a year's worth of doses from her local clinic or pharmacy and then control her own contraceptive use, which is going to reduce her time away from home, work, or other activities.

It seems like an amazing thing to put the choices in the hands of women themselves.

It really is. And we're starting to see new models emerge on questions like: How do you coach health care workers to coach women? How do we put products in places they've never been before? How do we enable contraceptive use by putting things on YouTube to say, here's how to do that injection yourself? It is really a game changer. It’s super exciting.

Stephanie Desmon is the co-host of the Public Health On Call podcast. She is the director of public relations and marketing for the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs, the largest center at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.