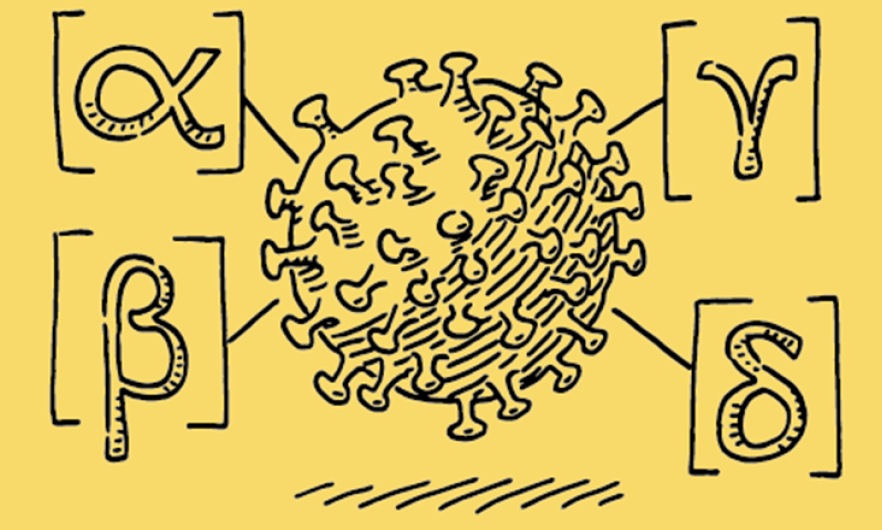

What the Delta Variant Means for Vaccinated and Unvaccinated People

What people should be most concerned about at this point

Q&A BY LINDSAY SMITH ROGERS

There are a lot of worrying headlines about the delta variant and outbreaks of COVID-19 around the world, but what’s the most concerning?

In this Q&A, excerpted from a July 1 episode of Public Health On Call, epidemiologist Jennifer Nuzzo, DrPH, SM, from the Center for Health Security answers questions about delta’s transmissibility and whether it causes more severe disease, what the variant means for both vaccinated and unvaccinated people, and what everyone should take away from recent headlines.

In light of the delta variant of COVID, the WHO recently released a statement urging that fully vaccinated people continue to wear masks and practice social distancing. This seems to run counter to a lot of the messaging that vaccines are so effective. How can we think about this?

I think that statement is issued in a global context, where there are incredible disparities in terms of access to vaccines.

If you're fully vaccinated and living in a place where case numbers continue to fall because there's a high vaccination coverage, I personally would feel safe going maskless in those circumstances.

We know that vaccines are incredibly good at preventing people from becoming ill with the virus and getting clinical COVID-19. We also know that if they do become infected, and maybe not even have symptoms, or have mild symptoms, that they're probably less likely to transmit it. So, vaccines are also good at reducing transmission. I don't want to undersell the vaccines here.

That said, particularly if you're living in a high incidence environment—a place where there's a lot of COVID circulating—adding a mask in crowded indoor spaces is just an added layer of protection. I sometimes do that when I'm with my kids, because they still have to wear masks and they're not vaccinated. And also, it has become a bit of a habit, but I don't want to undersell the importance of vaccines. They're doing remarkable work. And the safest way to protect yourself is to get vaccinated.

There's still some debate over just how contagious or more contagious the delta variant is. Why is that?

There's fairly clear evidence that the delta variant spreads faster. So, when people get infected, they're capable of infecting more people and we accumulate more cases in a given period of time with delta. That's concerning, because it means that some places that have been really good at controlling the spread of COVID through traditional public health tools, like testing and isolation and contact tracing, are having a harder time keeping up with the spread of the virus. So, you're seeing places that maybe didn't have to shut down [before], and now whole cities or parts of a country are having to do that. So that's why this variant is so worrisome.

But for someone who is fully vaccinated, I don't think you necessarily have to fear more. We know that vaccines still offer good protection against infection and illness.

What do we know at this point about whether or not delta causes more serious illness?

That's a particularly controversial point. There have been some observations that perhaps it does, [but] it's really hard to do those studies to tell if, in fact, it's the virus that's making people more ill than previous forms of the virus or just the population in which the virus is circulating and the stress on hospitals when you have more cases to deal with.

I personally think just the prospect that the virus could make people more ill warrants concern. It's hopefully quite motivating to get vaccinated, so you just don't even have to worry about that.

What do we need to know about delta plus, which is a slight variation of the delta variant?

I think it's still too early to say. But the overarching message is the same: The longer we allow this virus to circulate in high numbers across the planet, the more we're going to continue to hear about new mutations, and the more we're going to have to wonder what these new mutations mean. And the more possibility there is for new mutations to potentially render our vaccines less effective.

So far, we haven't really seen that in a way that's that concerning, but there are no guarantees. If we want to stop hearing about new variants—a “variant of the week”—then what we really need to do is make sure that all countries have access to the vaccines they need to protect their high-risk populations and adults.

Let's talk about some specific scenarios. In Australia, there were reports of a birthday party where every unvaccinated person got sick, and stories of people getting infected from just five to 10 seconds of a stranger walking by them. What's going on here?

Australia is in a really interesting situation. They have done quite well at keeping their case numbers low and they've done so at considerable cost. They really limited who can come into the country and subject people when they do come to hotel-based quarantine. Unfortunately, it hasn't been perfect. And with the delta variant having the ability to infect more people over the same period of time compared to the previous versions of the virus, they've been having a hard time keeping up [in terms of] putting a ring around these cases and preventing them from spreading.

So, now we're seeing parts of Australia having to lock down, including Australia's largest city, Sydney. What this really tells us is that, first of all, the delta variant is moving faster than the efforts to stop the spread through traditional public health means. Australia is also in an unfortunate circumstance of having very low vaccination coverage in its population. It’s really a wake-up call for countries that the fastest path to normalcy is through vaccination.

Of course, many countries very much want to do that, but don't have access to vaccines. That's why it's so important that we work to improve vaccine equity and make sure that all countries have access, because otherwise countries are [left] essentially unprotected.

What about Israel, for example, which does have very widespread vaccination: There was an outbreak of delta where 50% of adults that tested positive were fully vaccinated. But that situation might be a little misleading. Can you talk to us about that?

One of the challenges in tracking these infections after vaccination is that we can't just say, “Did you test positive?” We also have to wonder if people are sick [and] if they have any symptoms. My understanding of that situation is that the majority don't have any symptoms whatsoever.

The U.S. CDC doesn't recommend that people who've been fully vaccinated even be tested unless they have symptoms. The concern is, what [does] a positive test mean? For somebody who's fully vaccinated and doesn't have symptoms, there's some possibility that perhaps they're going through the natural immune response to the virus and not necessarily going to become sick or capable of transmitting their infection to others.

What I take away from it is that these vaccines are doing exactly what we expect them to do, which is keeping people from getting sick. That's my goal for this virus: that we use vaccines to tame this virus and to take off the table its ability to make people sick [enough] to put them into hospitals or to kill them. If this virus could only make people infected, but with no symptoms, or infected with very mild symptoms, we would have never heard of it. We have to remind ourselves what the overarching goal here is, which is to end this crisis through vaccination, so that this virus doesn't severely harm people in the way that it has for the last year and a half.

So, it seems like some of these scary headlines can be contextualized as concerning, but maybe not a full-blown crisis at this point. But there are some much more worrying outbreaks across Africa and Southeast Asia. What's different about these scenarios?

When we're talking about genetic variants, the overarching message—the point of concern—isn't “What does it mean for people who are vaccinated?” It means: “How can we work even harder to make sure others on the planet have access to vaccines so that they too can protect themselves, and so that we can reduce the likelihood of new genetic variants emerging.”

To me, that is the takeaway in all of these headlines. Unfortunately, we are not making enough progress on that and what we are seeing is really deadly epidemics occurring in multiple parts of the world. We are seeing [this] even in countries that had previously been very successful at controlling COVID through targeted public health measures—testing, contact tracing, isolation and quarantine. A number of places are really struggling to keep up, in part because of the added transmissibility of some of the newer variants. It really underscores the urgency of making sure that these countries can access vaccines and protect their adult populations to prevent serious illnesses from occurring, but also to reduce the spread of this virus and to reduce the likelihood that new additional variants will emerge. That is the fundamental takeaway in all of this.

We are incredibly fortunate here in the United States to have access to ample quantities of vaccines to protect ourselves, and we are very much seeing the benefits of that where our case numbers have been falling. I, of course, do worry about parts of the U.S. where vaccine coverage isn't high, and we could see a surge of cases later in the summer or early fall. I don't worry that we're ever going to get back to the levels of infection that we were at in the winter months, because we do, overall, have a high level of vaccine coverage. But I really think it's a tragedy for anyone in the United States—where we have access to ample quantities of vaccines—to get infected with this virus and to wind up in the hospital or to die from that infection when it simply could have been prevented by getting vaccinated.

My worry for the fall is that there should not be any more loss of life or health because of this virus, given our relative fortune in having access to vaccines in a way that so many countries don't, and so many countries should.

There are many states right now that have less than 35% of adults vaccinated, including Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Wyoming. What do we know, at this point, about what delta is doing in areas like these?

It's hard to say. We are seeing a slowing in the decline of cases in the U.S. So, we have entered a period where our case numbers are starting to plateau. We've seen a plateau previously and we got past that, in part through the expansion of who could be vaccinated. Initially, if you remember, we started with generally older folks and as we continued to expand and reduce the age required for vaccination, we were able to break through that plateauing of our case numbers to see considerable declines.

Unfortunately, we are in a plateau and there are a few states that are actually headed in the wrong direction where their case numbers and hospitalizations are increasing and their rate of vaccinations is decreasing. One on my list this week is Missouri, where that is happening.

It's a little premature, I think, to say any rise in cases is due to delta, because we don't really conduct surveillance in a way that enables us to have that real-time monitoring of who is getting which variant. But, I think it absolutely is plausible that delta will make it harder to keep our case numbers down in the coming months in places where vaccine coverage is poor. So, it's really a plea to people: If you're not yet vaccinated and you're eligible, please do strongly consider going out to get it. I am a big fan of taking worries off of people's plates and this is one of the easiest ways to do that. If you're living in an area where there's low vaccination coverage, that's even more important because you don't have the benefit of a community level of protection

That means: Please, not only get yourself vaccinated, but talk to your loved ones, friends, and neighbors and encourage them. It helps everybody

Even if you've already had COVID, even if you're young and healthy, you should get vaccinated

Absolutely. I know some people who have already had COVID are particularly worried about getting vaccinated. The CDC recommendation is still that you do get vaccinated. We, of course, think that having prior COVID infection does give you some level of immunity, but it's hard to tell exactly how much because people have had different levels of infection or levels of illness from COVID. Some people have mentioned the possibility of [vaccination] triggering long COVID—that's not something to worry about.

For many people, especially the ones living in the U.S., it's the long-awaited “fully vaccinated summer” and folks want to travel, they want to see loved ones, and they want to relax after an incredibly difficult 14 months. For those of us that are fully vaccinated, what do we need to know about delta and what are some things we should be looking for if we want to let our guards down?

I'm not quite worried about Delta. If you're fully vaccinated, we still know that vaccines are incredibly effective against all forms of the virus that we have found so far. I think you can travel with a relative sense of security.

If you're like me, and you have kids who are too young to be vaccinated, it's a little bit more of a complicated question. I think it ultimately comes down to your risk tolerance as a parent. We value travel as a family and spending quality time together in a way that travel allows us to do. So, we will be traveling with my two young kids. They wear a mask when they're in public spaces and we continue to protect them in the same way that we've been doing for the last year. But we do think it's possible to take a trip as a family and do that safely, even though my two kids are too young to be vaccinated.

Jennifer Nuzzo, DrPH, SM is a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security and an associate professor in the department of Environmental Health and Engineering.

Lindsay Smith Rogers, MA, is the producer of the Public Health On Call podcast and the associate director of content strategy for the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

RELATED CONTENT

Public Health On Call

This Q&A is excerpted from the July 1 bonus episode of the Public Health On Call Podcast.