The Potential—and Limits—of Antibody Testing

The U.S. is at a critical stage in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Stay-at-home orders are now in place in 45 states, but many governors and legislatures are eager to begin lifting social distancing restrictions and reopening businesses.

But without knowing how many people have been exposed to the novel coronavirus, easing restrictions could be dangerous. Uneven availability of diagnostic testing has left officials in the dark about the actual extent of infections.

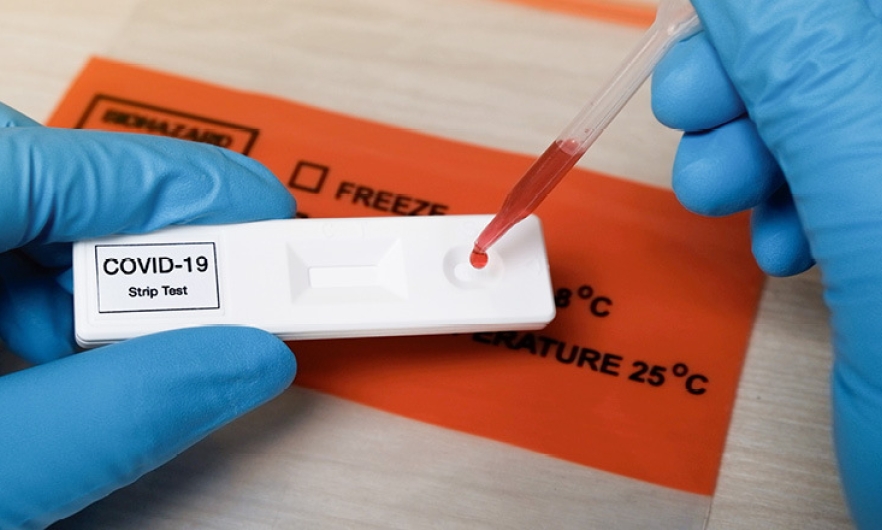

Gigi Gronvall, PhD, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security believes that serological tests, which detect antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 virus, could help fill that gap by identifying people who have been exposed to the virus. Widespread testing could tell us what percentage of the population has been exposed and potentially have at least some immunity to the virus.

But in a new report, Developing a National Strategy for Serology (Antibody Testing) in the United States, Gronvall and her colleagues show that significant work is still needed for serological tests to perform up to their potential.

First, the country needs accurate, validated tests. As of April 20, the Food & Drug Administration has issued Emergency Use Authorization for four different tests, effectively clearing them for clinical use. Some of these rapidly deliver a yes/no answer to indicate the presence of antiviral antibodies, such as the tests developed by Cellex and Chembio Diagnostic Systems. These tests give a straightforward answer to whether a person has previously been infected.

Other tests take longer, but provide measurements of antibody levels in an individual’s blood, such as the COVID-19 “enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay” developed at Mount Sinai Laboratory. Such readouts could help clinicians understand how antibody response correlates with severity of symptoms or help with the development of vaccines that maximize immunity. Patients with particularly strong antibody responses could also potentially serve as plasma donors—conveying potent immunity to critically ill patients struggling to overcome infection on their own.

Assistant Secretary of Health Brett Giroir has announced a cross-agency effort to validate currently available tests and benchmark their performance against each other. (While this effort is underway, clinicians and consumers must also be cautious of the myriad of unauthorized tests that have crept into the market without FDA oversight or approval.)

Until a vaccine is developed, robust serological testing could help guide plans for reopening. Gronvall cautions, however, that testing provides “useful information but not a magic open button for the world,” adding that “testing is just one tool” to use along with other public health tools. For example, workplace modifications—such as barriers between individuals, adequate ventilation, and frequent disinfection—can help ensure worker safety. The report also notes that reopening decisions should take into account local and regional trends in cases.

Some policy experts and analysts have floated the idea of immunity “passports” that certify antibody protection and allow people to return to public spaces. Gronvall notes that Germany, which has largely contained COVID-19, is still collecting data on the feasibility of this approach. She also expresses some concern that people might take risks, exposing themselves to infection as a ticket for leaving lockdown. “You don’t want to incentivize people getting the disease,” she says.

The biggest limits to realizing the potential of antibody testing are the many unknowns about this pathogen. For example, it’s not yet known whether antibodies confer immunity to the virus, or what level of response is necessary for immunity, or how long such protection might last.

This means that any recommendations about serological testing will remain a work in progress for the foreseeable future. Gronvall expects that the just-released report will likely need to be updated, as new information about the virus and the immune response to it becomes available every day.

“This is a research project going on in real time,” she says.

Michael Eisenstein is a science writer whose work has appeared in Nature, SEED, Wired Science, and Hopkins Bloomberg Public Health, among other publications.