Detained and Vulnerable to COVID-19

The U.S. detention centers that hold undocumented immigrants awaiting processing or a court date are primed for uncontrolled coronavirus transmission, say public health experts.

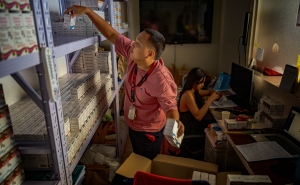

Effective social distancing is impossible, basic hygiene products such as soap and hand sanitizer are in short supply, and health care is minimal.

It’s a public health disaster in the making, and experts say it’s difficult at this point to gauge the extent of the problem.

“ICE [Immigration and Customs Enforcement] and CBP [Customs and Border Protection] are not transparent. You can’t count on them,” says Zackary Berger, MD, PhD, co-chair of the Maryland chapter of Doctors for Camp Closure—a group of more than 2,000 health care professionals advocating for proper medical care in detention centers.

“We have no idea who’s testing [for COVID-19] or if there’s testing. We don’t know how many cases have been diagnosed, and we won’t know the mortality rate,” says Berger, an associate professor who holds a joint appointment at the Bloomberg School and the Division of Internal Medicine at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

“I can paint very dark scenarios which might come to pass, but we probably won’t know until afterward,” says Berger, a core faculty with the Berman Institute of Bioethics at the Bloomberg School.

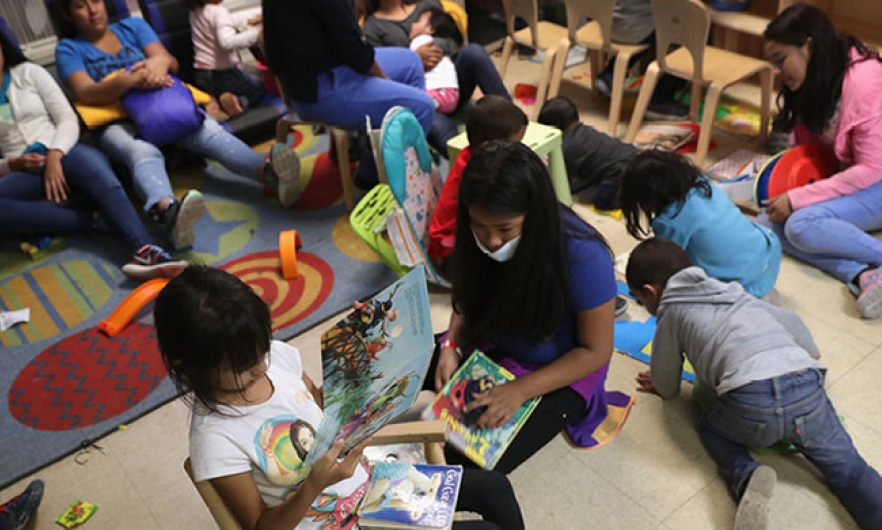

CBP centers are the first stop for undocumented immigrants arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border. The stated maximum holding period is 72 hours, though many arrivals are held for longer periods, say immigrant advocates. After CBP processing, ICE centers detain immigrants longer-term; they hold 37,000 detainees in a nationwide network of 200 facilities.

According to the CBP website, the agency is working with federal, state, and local agencies to “support the whole-of-government effort to slow the spread of COVID-19 and keep everyone safe.” The ICE website reports 11 confirmed COVID-19 cases in detention centers--six detainees and five staff--as of April 1, 2020.

Meanwhile, as news reports emerge of COVID-19 cases among ICE staff and detainees, immigration advocates, including the ACLU, are pursuing legal action to release detainees who are vulnerable to infection.

Berger describes the conditions at the border facilities as “squalid,” lacking sufficient restrooms, clean clothing, and personal hygiene supplies, and characterizes health care services at the “emergency-response” level.

“There are no trained health care providers on staff,” he says. “If help is needed, health aides call in a nurse or doctor.”

Many migrants and asylum seekers who enter CBP facilities arrive without proper vaccinations and suffer from often-untreated underlying conditions—worsened by the journey to the U.S.—that raise their risk for COVID-19 infection, says Alia Sunderji, MD, an MPH student and pediatric emergency physician at Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital, and a member of Doctors for Camp Closure.

Sunderji points out that fewer immigrants are being held at CBP facilities since the Trump administration tightened immigration measures with the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP)—also known as the “Remain in Mexico” program—which took effect in January 2019. But the policy has created a new set of health problems at the U.S.-Mexico border.

“You cross the border, you take a number, and as your paperwork is being processed you wait in Mexico in informal settlements that don’t have access to appropriate soap and water. But people have nowhere else to wait” says Sunderji.

Also at high risk of infection are undocumented immigrants living and working in the U.S. who may have COVID-19 symptoms but are unlikely to seek health care because of a general distrust of the U.S. government or a lack of health insurance. The Affordable Care Act does not cover undocumented immigrants, according to a March 27 commentary in the New England Journal of Medicine by Chris Beyrer, MD, MPH ’91, Desmond M. Tutu Professor of Public Health and Human Rights at the Bloomberg School, and Kathleen Page, MD, an associate professor at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

Although the U.S. Citizens and Immigration Services “encourages” undocumented immigrants to seek medical treatment or preventive services if they have COVID-19 symptoms, they are unlikely to follow that guidance, the authors write.

“Without a primary care provider to call, many uninsured immigrants will resort to online information, whether accurate or inaccurate,” according to the report. “Some will go to the ED, perhaps unnecessarily; and others will wait too long to seek care.”

The authors call for all COVID-19 health care to be covered and for “low-flight-risk immigrants to be released from detention.” These actions, write Beyrer and Page, “will not reverse but may mitigate COVID-19’s impact on undocumented immigrants and the health of the public at large.”

Jackie Powder is an assistant editor in the Communication & Marketing Office at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

RELATED CONTENT

More from the Bloomberg School

- See latest headlines

- Learn more about our departments: