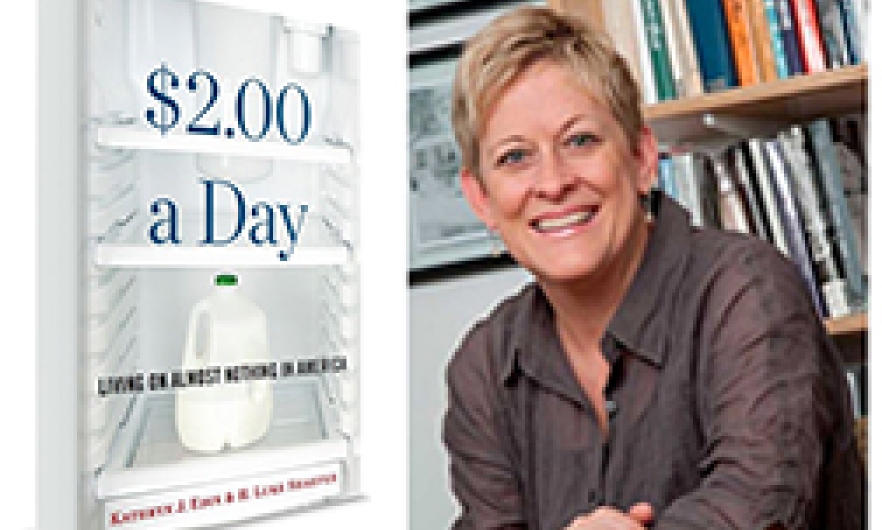

Baltimore Dialogue with Kathryn Edin: $2.00 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America

“It’s never been better for the working poor than it is now. But it’s never been worse for those at the ragged end of the poverty line,” said Kathryn Edin, speaking at a recent Baltimore Dialogue at Amazing Grace Lutheran Church.

Edin, a professor at Johns Hopkins University and author of the newly published $2.00 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America, is one of the nation’s leading poverty experts. Her new book describes the results of two decades’ research on American poverty. Although the research for her book took place in Chicago, Cleveland, eastern Tennessee and the Mississippi delta, Edin told the gathering, “This book is very much a Baltimore story.”

“Many of our states have no safety nets left. Tax credits only work if you’re working. You can’t actually live on $2 a day.” That reality, Edin said, is as true in Baltimore as it is in other parts of the country.

She described a major change in the last two decades in how the poorest of the poor survive. Welfare, once a safety net, has plummeted as many people no longer qualify for those benefits. In 2011, 1.5 million households with roughly 3 million children were surviving on cash incomes of no more than $2 per person, per day in any given month.

Many poor working families do receive tax credits and many more receive food stamps. But as Fidel Desir, a PhD student at Johns Hopkins and a Brown Scholar, noted, “With food stamps, you can’t pay the light bill. You can’t pay the rent. You can’t buy your kids underwear. You can’t buy the smart phone you need to apply for jobs.”

Edin told the story of a woman named Ashley, who received $50 in exchange for participating in the research study. She did not use the money for food or rent. She spent her money on a pantsuit and a perm, in order to polish her appearance for job interviews. Without money, Edin said, those kinds of purchases aren’t possible. “What does it mean to live with virtually no cash?”

Among those Edin documented as living on $2 a day, half were white; one quarter were black, and one quarter Latino. And while the focus is often on families headed by single mothers, one third of the households living in extreme poverty were headed by a married couple.

“These are people who want to work and who can’t get a job,” Edin said. “Unprecedented numbers of single mothers on welfare want to work. They are trying to work. They are saying, ‘If you have a job, I’m there.’ There aren’t even enough bad jobs to go around. We need a radical expansion of employment.”

Edin said she thinks the private sector can only do so much. “There’s an incredible catch-22. Americans are averse to welfare but we are also averse to taxation. If we’re going to create employment for all, then government is going to have to play a larger role.”

Another issue faced by the poorest families is lack of affordable housing, she said. “We have to address the affordable housing crisis. Every parent ought to be able to raise her children in a place of her own.”

Lack of jobs and lack of housing lead to myriad problems for families, ranging from wage theft (maids expected to clean additional rooms before or after their shifts) to poor nutrition (families in which everyone is scrambling for work and living in shared quarters are places where cooking “fades away,” Edin said).

When people participating in the Dialogue asked Edin how she thought they could help, she made two suggestions: obsessively tip anyone in the service industry and know how the businesses they deal with treat their employees.

UHI and Amazing Grace Lutheran Church present a new Baltimore Dialogue several times a year as a way to engage community members in discussions about living in Baltimore.

“This is not a lecture. This is not a book club. We use books that are relevant to Baltimore to talk about race, racism, power and privilege,” Robert Blum, UHI director.

Gary Dittman, pastor of Amazing Grace, was pleased by the turnout for the discussion on poverty. “We’re looking for ways to connect our worlds, ways to make our community healthier,” he said.